Receive our blog posts in your email by filling out the form at the bottom of this page.

What the world refers to as “Super Bowl Sunday” is not a designation that would have been countenanced by most 19th century Presbyterians. American football began in 1869, while professional football dates to 1920. So, of course, there was no Super Bowl around until well into the 20th century, but the issues of recreation, secularism and commercialism intruding into the Lord’s Day were well-known and widely addressed by Christians in the past.

American Presbyterians, who held to the understanding of the Fourth Commandment articulated in the Westminster Standards, believed that the whole day — that is, the first day of the week — should be devoted to the worship of God, which involves works of piety, necessity and mercy— to the exclusion of “worldly employments and recreations” (Westminster Confession of Faith 21:6-7).

That understanding is important to today’s article, but even beyond that, when considering what is widely known today as “Super Bowl Sunday,” besides the question of the lawfulness of attending to such recreation, another point of discussion centers on the terminology involved.

If words mean something — think of the words homoousios (“of the same substance” or “of the same essence”) and homoiousios (“of like essence”) and their meaning in the context of the great Arian controversy of the 4th century AD — then as Christians who are to take “into captivity every thought to the obedience of Christ” (2 Cor. 10:5), we may wish to consider the voices of those in the past who have argued that the term “Sunday” is not a desirable or Biblical designation for the first day of week, much less “Super Bowl Sunday.”

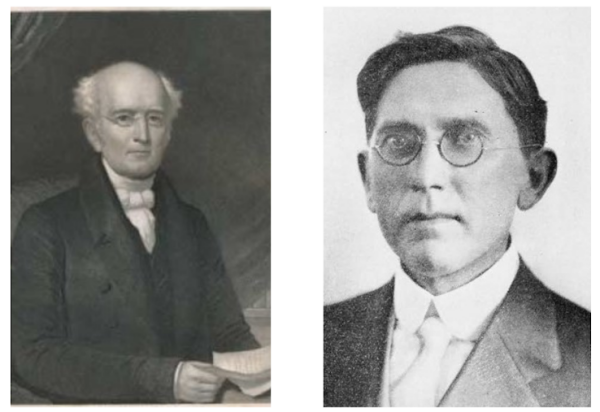

First, let us hear Samuel Miller, the great defender of historic Presbyterianism from Princeton, who authored an 1836 article titled “The Most Suitable Name For the Christian Sabbath.” After addressing the objection of Quakers to the word “Sunday” (they believed the fourth commandment was abrogated and preferred to use the phrase “the first day of the week”), Miller turned his attention to the pagan origin of the term “Sunday.” After discussion of the history of the Christian observance of the first day of the week and its relationship to the Jewish Sabbath and the pagan Sunday, Miller sums up his position in a few succinct paragraphs:

We are now prepared to answer the question, “What name ought to be given to this weekly season of sacred rest, by us, at the present day?”

Sunday, we think, is not the most suitable name. It is, confessedly, of Pagan origin. This, however, alone, would not be sufficient to support our opinion. All the other days of the week are equally Pagan, and we are not prepared to plead any conscientious scruples about their use. Still it seems to be in itself desirable that not only a significant, but a scriptural name should be attached to that day which is divinely appointed; which is so important for keeping religion alive in our world; and which holds so conspicuous a place in the language of the Church of God. Besides, we have seen that the early Christians preferred a scriptural name, and seldom or never used the title of Sunday, excepting when they were addressing the heathen, who knew the day by no other name. For these reasons we regret that the name Sunday has ever obtained so much currency in the nomenclature of Christians, and would discourage its popular use as far as possible.

The Lord’s day, is a title which we would greatly prefer to every other. It is a name expressly given to the day by an inspired apostle. It is more expressive than any other title of its divine appointment; of the Lord’s propriety in it; and of its reference to his resurrection, his triumph, and the glory of his kingdom. And, what is in no small degree interesting, we know that this was the favourite title of early Christians; the title which has been habitually used, for a number of centuries, by the great majority both of the Romish and Protestant communions. Would that its restoration to the Christian Church, and to all Christian intercourse, could be universal!

The Sabbath, is the last title of which we shall speak. The objections made to this title by the early Christians no longer exist. We are no longer in danger of confounding the observance of the first day of the week with that of the seventh. Nor are we any longer in danger of being carried away by a fondness for Jewish rigour, in our plan for its sanctification. The fourth commandment still makes a part of the Decalogue. We teach it to our children as a rule still in force. It requires nothing austere, punctilious, or excessive; only that we, and all “within our gates,” abstain from servile labour, and consider the day as “hallowed,” or devoted to God. Whoever scrutinizes its contents will find no requisition in which all Christians are not substantially agreed; and no reason assigned for its observance which does not apply to Gentiles as well as Jews. As the first sabbath was so named as a memorial of God’s “rest” from the work of creation; so we may consider the Christian Sabbath as a memorial of the Saviour’s rest (if the expression may be allowed) from the labours, the sufferings, and the humiliation of the work of redemption. And, what is no less interesting, the apostle, in writing to the Hebrews, considers the Sabbath as an emblem and memorial of that eternal Sabbatism, or “rest which remaineth for the people of God.” Surely the name is a most appropriate and endeared one when we regard it in this connection! Surely when we bring this name to the test of either philological or theological principles, it is as suitable now, as it could have been under the old dispensation.

We have said, that we prefer “the Lord’s day” to any other title. We are aware, that this can never be the name employed by the mass of the community. There is something about this title which will forever prevent it from being familiar on the popular lip. The title “the Sabbath” is connected with no such difficulty. It is scriptural, expressive, convenient, the term employed in a commandment which is weekly repeated by millions, and so far familiar to all who live in Christian lands, that no consideration occurs why it may not become universal. “The Lord’s day” may, and, perhaps, ought ever to be, the language of the pulpit, and of all public or social religious exercises; meanwhile, if the phrase “the Sabbath” could be generally naturalized in worldly circles, and in common parlance, it would be gaining a desirable object.

A later Reformed Presbyterian (Covenanter) minister, Thomas M. Slater, covered much of the same ground in a tract titled “Nicknaming the Sabbath: A Protest Against Using Other Than Scriptural Names For the Lord's Day.” He too addressed the pagan nature of the term “Sunday” and argues that its usage is an affront to the Lord who set his name upon the first day of the week. For Slater, too, there was significance in the choice of terminology which ought not to be overlooked.

We grant that many sincere Christians have always called the Lord's day “Sunday,” not because they deliberately adopted that name for the Sabbath, but because they have always heard it so called, and never knew any serious objection to its use. But if such persons will reflect that “Sunday” is not the name by which God calls His day; that we have been given no authority to set aside His prescription; that this nickname originated among the foes of the Lord's day; that it was not adopted by Christians at all until pagan ideals invaded Christianity; that it has always been repudiated by a witnessing remnant of the friends of the Sabbath; and been favored by advocates of a secular day -- if a Christian who has a sincere desire to please God candidly weighs all that “Sunday” stands for, over against that all that the Scriptural names stand for, he will without question choose to call the Holy Day by its holy name, to the exclusion of all others. For “speech is the correlate of thought.”

Slater, like Miller, in the vein of Puritans before them who were sometimes known derisively as “Precisionists,” argued for expressions of thought grounded in Biblical principle, especially in a matter which Presbyterians of an earlier time viewed the importance of the Sabbath in its relation to both to the church and to civil society. It was not long before the first “Super Bowl Sunday” was held in 1967 that the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) issued this relevant warning:

Let us beware brethren: As goes the Sabbath, so goes the church, as goes the church, so goes the nation [emphasis added]. Any people who neglect the duties and privileges of the Sabbath day soon lose the knowledge of true religion and become pagan. If men refuse to retain God in their knowledge; God declares that He will give them over to a reprobate mind. Both history and experience confirm this truth” (Minutes of the Sixty-First General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States, A.D. 1948, p. 183).

If words really have particular meaning, we would do well to consider the counsel of these voices from the past and take a counter-cultural approach to our choice of terminology as it pertains to the holy day of God’s appointment. The religious devotion of many to “Super Bowl Sunday” does not go unnoticed. Can it be said of Christians that the “Lord’s Day” or the “Christian Sabbath” speaks to their devotion in equally apropos terms?