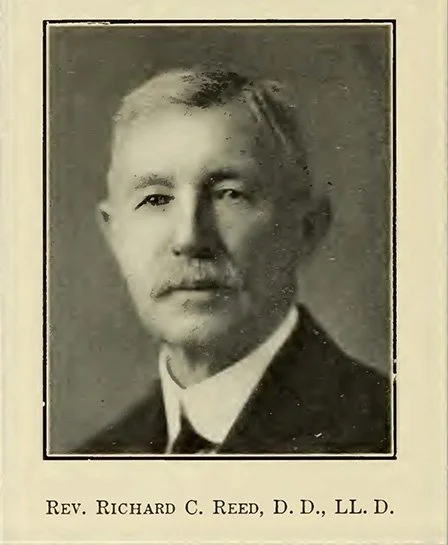

Richard Clark Reed, Southern Presbyterian minister and theologian, died 100 years ago on this day in history, July 9, 1925, in Columbia, South Carolina.

Born on January 24, 1851 in Harrison, Tennessee, Richard Clark Reed was educated at King College (1873) and at Union Theological Seminary in Richmond, Virginia (1876).

His pastoral ministry began in 1877, when he was ordained and installed as the pastor of the Presbyterian Church at Charlotte Court House, Virginia, where he served for eight years. He ministered in Franklin, Tennessee for four years. He served as pastor of the Second Presbyterian Church in Charlotte, North Carolina from 1889 to 1892; and as pastor in Nashville, Tennessee from 1892 to 1898. In 1898, he accepted the chair of Church History, and Church Polity, in Columbia Theological Seminary, and served there until his death. He also served as Moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) in 1922.

He was the author of many articles and some books, including The Gospel as Taught by Calvin (1896); History of the Presbyterian Churches of the World: Adapted For Use in the Class Room (1905); and What is the Kingdom of God? (1922). Reed's History of the Presbyterian Churches of the World served as the inspiration for James E. McGoldrick of Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary when he published Presbyterian and Reformed Churches: A Global History (2012). Reed also served as an editor at The Presbyterian Quarterly and at The Presbyterian Standard.

William M. McPheeters eulogized of him thus: "When his name is mentioned, the first picture that it will bring before our minds will unquestionably be that of Dr. Reed the man, the Christian man and minister. It was in that character that we knew, admired, and loved him. His fine presence, his modest, unassuming bearing, his genial and sunny disposition, his kindly interest in his fellows, his cheerfulness that was never permitted to degenerate into frivolity, his sobriety unmarred by the least taint of morbidness, his wisdom in counsel, his poise and patience under opposition, his tact in dealing with a delicate situation, his reverence, his filial confidence in God, his devotion to his Redeemer, his humble-mindedness before God, his readiness, as one who had himself freely received, freely to give his time, his sympathies, strength for the benefit of others — what a long list of admirable qualities it is! And I might add others. No wonder such qualities greatly endeared Dr. Reed to those who knew him. Together they constitute a picture to which memory will delight to recur and in dwelling upon which it will find heart's ease and inspiration."

We remember him today one full century after he entered into glory.

John Rodgers Davies: A "Wond'rous Miniature of Man"

Receive our blog posts in your email by filling out the form at the bottom of this page.

Be deeply affected with the corruption of nature in your children. For as no man will value a Savior for himself who is not convinced of the sin and misery which he must be saved from, so you must be sensible of your children’s sins, or else you cannot labor for their salvation. When your sweet babes are born, you rejoice to find that in God’s book all their members are written. But you should be sensible of that body of sin they are born with, and that by nature they are young atheists and infidels, haters of God, blasphemers, whoremongers, liars, thieves, and murderers. For they are naturally inclined to these and all other sins, and are by nature children of the wrath of the infinite God. And being convinced of us, you will find that your chief care of them should be to save them from this dreadful state of sin and misery. — Edward Lawrence, Parents’ Concerns For Their Unsaved Children (1681, 2003), p. 33

This little story may not have a happy ending; not all stories do. Only the Searcher of hearts knows the full story though.

Samuel Davies, the great Presbyterian “Apostle of Virginia” and President of the College of New Jersey (Princeton), who himself — like his Biblical namesake — was a "child of prayer," was married twice. His first wife, Sarah Kirkpatrick, died in childbirth in September 1747, along with their infant son, less than one year after the couple was married. Davies married Jane Holt of Williamsburg in October 1748, and they had a total of six children — three boys who survived to adulthood, two daughters likewise, and one daughter who died in infancy.

On August 20, 1752, John Rodgers Davies, named for a dear friend of Samuel, John Rodgers (1727-1811), entered the world. His father wrote a poem upon the occasion: "On the Birth of John Rodgers Davies, the Author's Third Son."

Thou little wond'rous miniature of man,

Form'd by unerring Wisdom's perfect plan;

Thou little stranger, from eternal night

Emerging into life's immortal light;

Thou heir of worlds unknown, thou candidate

For an important everlasting state,

Where this your embryo shall its pow'rs expand,

Enlarging, rip'ning still, and never stand....

Another birth awaits thee, when the hour

Arrives that lands thee on th'eternal shore;

(And O! 'tis near, with winged haste 'twill come,

Thy cradle rocks toward the neighb'ring tomb;)...

A being now begun, but ne'er to end,

What boding fears a father's heart torment,

Trembling and armons for the grand event,

Lest thy young soul so late by heav'n bestow'd

Forget her father, and forget her God!...

Maker of souls! Avert so dire a doom,

Or snatch her back to native nothing's gloom!

Davies treasured his children as gifts of God for which he and Jane were designated stewards, assigning great worth to their eternal souls, and thus took great pains in his household to lead family worship and to educate his children himself.

"There is nothing," he writes to his friend, "that can wound a parent's heart so deeply, as the thought that he should bring up children to dishonor his God here, and be miserable hereafter. I beg your prayers for mine, and you may expect a return in the same kind." In another letter he says, "We have now three sons and two daughters, whose young minds, as they open, I am endeavoring to cultivate with my own hand, unwilling to trust them to a stranger; and I find the business of education much more difficult than 1 expected. My dear little creatures sob and drop a tear now and then under my instructions, but I am not so happy as to see them under deep and lasting impressions of religion; and this is the greatest grief they afford me. Grace cannot be communicated by natural descent; and if it could, they would receive but little from me." — John Rice Holt, Memoir of the Rev. Samuel Davies (1832), p. 106

One might think that the children of such a humble, godly minister of the gospel as Samuel Davies was known to be might excel in piety themselves. The picture we are given of their trajectories in life is not as inspiring as we would wish, however.

Jane Holt Davies, known to Samuel affectionately as "Chara" (Greek for joy or happiness), is believed to have died in Virginia sometime after 1785.

William (b. August 3, 1749) served in the American army in the War of Independence and rose to the rank of colonel. He was a man of gifted intellect, but of "loose and unsettled" religious opinions.

From this gentleman [Capt. William Craighead] the writer learned that Col. Davies always spoke with high respect of the character and talents of his father; but his own religious opinions seemed to be loose and unsettled. He expressed the opinion that the Presbyterian religion was not well adapted to the mass of mankind, as having too little ceremony and attractiveness; and, on this account, he thought the Romanists possessed a great advantage. He was never connected, so far as is known, with any religious denomination; and, it is probable, did not regularly attend public worship. His death must have occurred before the close of the last century, but in what particular year is not known. He died, however, in the meridian of life.*

Samuel (b. September 28, 1750), who in appearance resembled his father and namesake, was "indolent" in business and ultimately moved to Tennessee where he died in obscurity.

The only child of Samuel Davies who made a public profession of faith was a daughter who lived in the Petersburg, Virginia area.

Concerning John Rodgers Davies, the report we have is not encouraging.

The third son, John R. Davies, was bred a lawyer, and practised law in the counties of Amelia, Dinwiddie, Prince George, &c. He was a man of good talents, and succeeded well in his profession; but he had some singularities of character, which rendered him unpopular. As to religion, there is reason to fear that he was sceptical, as he never attended public worship, and professed never to have read any of his father’s writings. An old lady of the Episcopal church, in Amelia, informed the writer, that he frequented her house, and was sociable, which he was not with many persons. As she had heard his father preach, had derived profit from his ministry, and was fond of his printed sermons, she took the liberty of asking Mr. Davies whether he had ever read these writings. He answered that he had not. At another time she told him that she had one request to make, with which he must not refuse compliance. He promised that he would be ready to perform any thing within his power to oblige her. Her request was that he would seriously peruse the poem which his father wrote on the occasion of his birth. “Madam,” said he, “you have imposed on me a hard service.” Whether he ever complied with the request is not known. About the year 1799 the writer was in Sussex county, and in the neighbourhood where this gentleman had a plantation, on which he had recently taken up his residence. Those of the vicinity, who professed any religion, were Methodists; their meetings however he never attended, always giving as a reason that he was a Presbyterian. But now a Presbyterian minister had come into the neighbourhood, and was invited to preach in a private house, almost within sight of Mr. Davies; he was informed of the fact, and was earnestly requested to attend. He declined on one pretext or another; but on being importuned to walk over and hear one of his own ministers, he said, “If my own father was to be the preacher, I would not go.” And again, “If Paul was to preach there, I would not attend.”*

John Rodgers Davies died unmarried in Virginia in 1832. There is no indication in the historical record that he ever embraced the faith of his father.

As Davies said, "Grace cannot be communicated by natural descent." It is undoubtedly a great blessing for children to be raised in a godly home. Although covenant promises give us great reason to hope, there is no guarantee that godly parents will necessarily have godly children. He died in 1761 so the oldest of his children, William, would have been but eleven years old, and the lack of fatherly guidance in their teenage years is factor not to be ignored when taking stock of the childrens’ spiritual state in adulthood. But however the state of affairs may fall out in God’s providence, we must always pray for our children, and never give up hope for them, but trust in God for the salvation of their souls. He alone can give the gift of faith, and that should bring us to our knees as we pray for the good of those souls to which parents are entrusted as stewards.

* Source: A Recovered Tract of President Davies (1837).

Calvin on the Edge of Eternity

Receive our blog posts in your email by filling out the form at the bottom of this page.

It was not the head but the heart which made him a theologian, and it is not the head but the heart which he primarily addresses in his theology. – B.B. Warfield, John Calvin: The Man and His Work (1909)

The great Reformer John Calvin died on this day in history, May 27, 1564, in Geneva, Switzerland. He was only 54 years old; although he had suffered many maladies, yet had he accomplished so much in his lifetime to effect Reformation in the areas of worship, theology and civil government; in Geneva, Europe and even across the Atlantic, in sending missionaries to Roman Catholic France and to the New World; and inspiring settlers who risked all to follow them.

Today, we recall his final days as told by some authors on Log College Press who admired this great man.

Thomas Cary Johnson, John Calvin and the Genevan Reformation (1900), p. 87:

He preached for the last time on the 6th of February, 1564; he was carried to church and partook of the communion for the last time on the 2d of April, in which he acknowledged his own unworthiness and his trust in God's free election of grace and the abounding merits of Christ; he was visited by the four syndics and the whole Little Council of the republic on the 27th of April, and addressed them as a father, thanking them for their devotion, begging pardon for his gusts of temper, and exhorting them to preserve in Geneva the pure doctrine and government of the gospel; he made a similar address to all the ministers of Geneva on the 28th and took an affectionate leave of them; he had these ministers to dine in his house on the 19th of May, was himself carried to the table, ate a little with them and tried to converse, but growing weary had to be taken to his chamber, leaving with the words, 'This wall will not hinder my being present with you in spirit, though absent in the body.' [William] Farel (in his eightieth year) walked all the way to Geneva from Neuchatel to take leave of the man whom he had compelled to work in Geneva, and whose glorious career he had watched without the least shadow of envy.

With the precious word of God, which he had done so much to make plain to his own and all subsequent ages, in his heart and on his tongue, he died on the 27th of May, 1564.

Thomas Smyth, Calvin and His Enemies: A Memoir of the Life, Character, and Principles of Calvin (1856), pp. 77-82, elaborates on the story of the “last act” in Calvin’s life:

Let us, then, before we take our leave, draw near, and contemplate the last act in the drama of this great and good man's life. Methinks I see that emaciated frame, that sunken cheek, and that bright, ethereal eye, as Calvin lay upon his study-couch. He heeds not the agonies of his frame, his vigorous mind rising in its power as the outward man perished in decay. The nearer he approached his end, the more energetically did he ply his unremitted studies. In his severest pains he would raise his eyes to heaven and say, How long, Lord! and then resume his efforts. When urged to allow himself repose, he would say, 'What! would you that when the Lord comes he should surprise me in idleness?' Some of his most important and laboured commentaries were therefore finished during this last year.

On the 10th of March, his brother ministers coming to him, with a kind and cheerful countenance he warmly thanked them for all their kindness, and hoped to meet them at their regular Assembly for the last time, when he thought the Lord would probably take him to himself. On the 27th, he caused himself to be carried to the senate-house, and being supported by his friends, he walked into the hall, when, uncovering his head, he returned thanks for all the kindness they had shown him, especially during his sickness. With a faltering voice, he then added, 'I think I have entered this house for the last time,' and, mid flowing tears, took his leave. On the 2d of April, he was carried to the church, where he received the sacrament at the hands of [Theodore] Beza, joining in the hymn with such an expression of joy in his countenance, as attracted the notice of the congregation. Having made his will on the 27th of this month, he sent to inform the syndics and the members of the senate that he desired once more to address them in their hall, whither he wished to be carried the next day. They sent him word that they would wait on him, which they accordingly did, the next day, coming to him from the senate-house. After mutual salutations, he proceeded to address them very solemnly for some time, and having prayed for them, shook hands with each of them, who were bathed in tears, and parted from him as from a common parent. The following day, April 28th, according to his desire, all the ministers in the jurisdiction of Geneva came to him, whom he also addressed: 'I avow,'' he said, 'that I have lived united with you, brethren, in the strictest bonds of true and sincere affection, and I take my leave of you with the same feelings. If you have at any time found me harsh or peevish under my affliction, I entreat your forgiveness.' Having shook hands with them, we took leave of him, says Beza, 'with sad hearts and by no means with dry eyes.'

'The remainder of his days,' as Beza informs us, 'Calvin passed in almost perpetual prayer. His voice was interrupted by the difficulty of his respiration; but his eyes (which to the last retained their brilliancy,) uplifted to heaven, and the expression of his countenance, showed the fervour of his supplications. His doors,' Beza proceeds to say, 'must have stood open day and night, if all had been admitted who, from sentiments of duty and affection, wished to see him, but as he could not speak to them, he requested they would testify their regard by praying for him, rather than by troubling themselves about seeing him. Often, also, though he ever showed himself glad to receive me, he intimated a scruple respecting the interruption thus given to my employments; so thrifty was he of time which ought to be spent in the service of the Church.'

On the 19th of May, being the day the ministers assembled, and when they were accustomed to take a meal together, Calvin requested that they should sup in the hall of his house. Being seated, he was with much difficulty carried into the hall. 'I have come, my brethren,' said he, 'to sit with you, for the last time, at this table.' But before long, he said, 'I must be carried to my bed;' adding, as he looked around upon them with a serene and pleasant countenance, 'these walls will not prevent my union with you in spirit, although my body be absent.' He never afterwards left his bed. On the 27th of May, about eight o'clock in the evening, the symptoms of dissolution came suddenly on. In the full possession of his reason, he continued to speak, until, without a struggle or a gasp, his lungs ceased to play, and this great luminary of the Reformation set, with the setting sun, to rise again in the firmament of heaven. The dark shadows of mourning settled upon the city. It was with the whole people a night of lamentation and tears. All could bewail their loss; the city her best citizen, the church her renovator and guide, the college her founder, the cause of reform its ablest champion, and every family a friend and comforter. It was necessary to exclude the crowds of visitors who came to behold his remains, lest the occasion might be misrepresented. At two o'clock in the afternoon of Sabbath, his body, enclosed in a wooden coffin, and followed by the syndics, senators, pastors, professors, together with almost the whole city, weeping as they went, was carried to the common burying ground, without pomp. According to his request, no monument was erected to his memory; a plain stone, without any inscription, being all that covered the remains of Calvin.

Such was Calvin in his life and in his death. The place of his burial is unknown, but where is his fame unheard?

The actual precise location of John Calvin’s grave is unknown, but this spot in the Cimetière de Plainpalais in Geneva honors his memory.

And thus a great man lived and died, although unwilling to have his earthly remains become a shrine, yet leaving a legacy that many still cherish.

Note: This is an updated version of a post that was first published on May 27, 2018.

William H. McGuffey Entered Into Glory 150 Years Ago

Receive our blog posts in your email by filling out the form at the bottom of this page.

The young are on the voyage of life; the old have reached the harbor. - William H. McGuffey

It was 150 years ago today on May 4, 1873 that Presbyterian minister and educator William Holmes McGuffey entered into glory. Author of McGuffey’s Readers, his name lives on in many ways, and today we remember the man who has been referred to as “America’s Schoolmaster.”

Born on September 23, 1800, in Washington County, Pennsylvania, to a family of Scottish emigrants, he was educated at Greersburg Acadamey in Darlington, Pennsylvania. By the age of 14, he was working as a teacher in a one-room schoolhouse in Calcutta, Ohio. In 1826, he graduated from Washington College in Washington, Pennsylvania, and went on to join the faculty there. Three years later, he was ordained as a Presbyterian minister by Robert H. Bishop.

After teaching at Washington College, he joined the faculty of Miami University at Oxford, Ohio. In 1836, he became President of Cincinnati College. Three years later, he became President of Ohio University. In 1843, he became President of the Woodward Free Grammar School in Cincinnati. After serving as a professor at Woodward College from 1843 to 1845, he accepted an invitation to serve as the chair of moral philosophy and political economy in the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia, where he remained for the rest of his life.

It was in 1835, while teaching at Miami University — at the recommendation of his friend Harriet Beecher Stowe — that a Cincinnati publisher asked him to to create a series of four graded readers for young students. Thus, the eclectic series of McGuffey’s Readers was born. He authored the first four readers, while his brother Alexander H. McGuffey authored two more after that. These volumes were the first early reading books to gain wide-spread popularity in the American educational system. The series consisted of stories, poems, essays, and speeches. They included extracts from John Milton, Lord Byron, Daniel Webster and other highly-regard writers, as well as frequent allusions to the Bible. From 1836 to 1960, over 120 million copies were sold, and they remain in print today. They were a favorite of Henry Ford who in 1934 relocated the actual Pennsylvania log cabin where McGuffey was born to Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan to create a McGuffey schoolhouse. Frequently seen in the popular TV show, Little House on the Prairie, McGuffey’s Readers have long been a household name symbolizing Christian education, much like Noah Webster’s Dictionary.

McGuffey spent nearly three decades in Charlottesville where an elementary school built in 1915 was named after him (it is now known as the McGuffey Art Center). His name adorns other institutions and buildings, and a state in his honor can be seen at Miami University. After he died there was some talk of burying his body alongside that of his first wife, Harriet, who in 1850 was buried in Dayton, Ohio, but the University of Virginia prevailed upon his family to have his earthly remains laid to rest at the University of Virginia Cemetery and Columbarium.

For McGuffey, the bond between religion and education was sacred. Christians were people of the Book, and education was essential to reading the Scriptures and understanding the world which God made. We are thankful for his labors in promoting both education and the Christian religion in a busy, productive life on earth, which came to a peaceful end 150 years ago today.

Jonathan Edwards Remembered

Receive our blog posts in your email by filling out the form at the bottom of this page.

You are pleased, dear Sir, very kindly to ask me, whether I could sign the Westminster Confession of Faith, and submit to the Presbyterian form of Church Government; and to offer to use your influence to procure a call for me, to some congregation in Scotland. I should be very ungrateful, if I were not thankful for such kindness and friendship. As to my subscribing to the substance of the Westminster Confession, there would be no difficulty; and as to the Presbyterian Government, I have long been perfectly out of conceit of our unsettled, independent, confused way of church government in this land; and the Presbyterian way has ever appeared to me most agreeable to the word of God, and the reason and nature of things; though I cannot say that I think, that the Presbyterian government of the Church of Scotland is so perfect, that it cannot, in some respects, be mended. — Jonathan Edwards, The Works of President Edwards: With a Memoir of His Life (1830), Vol. I, p. 412 (Letter from Jonathan Edwards to John Erskine dated July 5, 1750)

Jonathan Edwards was not a Presbyterian, but as a leader in the Great Awakening his sentiments were favorable to Presbyterianism, and his life touched the lives of many authors on Log College Press, including the missionary David Brainerd, and his son-in-law, Aaron Burr, Sr.

As President of the College of New Jersey (Princeton), Edwards is closely associated with one of the great Presbyterian institutions in America and, in fact, was laid to rest at Princeton Cemetery. It was on this date in history, March 22, 1758, that Jonathan Edwards entered into glory. G.B. Strickler wrote (Jonathan Edwards [1903]):

…he was one of the most remarkable men the American church has produced, and as, although a Congregationalist, his history often touched and influenced that of the Presbyterian Church….

Historical marker located in South Windsor, Connecticut.

Edwards is widely thought of as America’s foremost theologian. John DeWitt spoke of him as “our greatest American Divine” (Jonathan Edwards: A Study [1904]). He was born on October 5, 1703, in East Windsor Connecticut. He had a spiritual awakening early in life, and after studying at Yale University, went on to serve as pastor of the church in Northampton, Massachusetts from 1727 to 1751. It was on July 8, 1741, that he preached one of the most famous sermons in American history: Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.

The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University today holds many of Edwards' surviving manuscripts, including over one thousand sermons, and other materials, and his works — which currently total 26 volumes — continue to be published. Some of the most significant include A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God in the Conversion of Many Hundred Souls in Northampton (1737); A History of the Work of Redemption (based on sermons preached in 1739, first published in 1774; see the 1793 edition published by David Austin here); The Distinguishing Marks of a Work of the Spirit of God (1741); A Treatise Concerning Religious Affections (1746); The Freedom of the Will (1754); and The Great Christian Doctrine of Original Sin Defended (1758). The 70 personal resolutions he wrote in his diary from 1722 to 1723 (300 years ago) have often been republished and have inspired countless thousands, if not millions.

Being sensible that I am unable to do anything without God’s help, I do humbly entreat him by his grace to enable me to keep these Resolutions, so far as they are agreeable to his will, for Christ’s sake.

1. Resolved, that I will do whatsoever I think to be most to God’s glory, and my own good, profit and pleasure, in the whole of my duration, without any consideration of the time, whether now, or never so many myriad’s of ages hence. Resolved to do whatever I think to be my duty and most for the good and advantage of mankind in general. Resolved to do this, whatever difficulties I meet with, how many and how great soever.

Following Burr’s death in 1757, Edwards assumed the presidency of the College of New Jersey on February 16, 1758, and immediate set an example to the students by getting a smallpox inoculation, as a result of which he died just over one month into his presidency. One month later, his daughter of Esther died, and later that same year, his wife Sarah also passed away.

Jonathan Edwards is buried at Princeton Cemetery, Princeton, New Jersey.

Henry C. McCook said this of one of his classic works (Jonathan Edwards as a Naturalist [1890]):

His work on “ The Will ” still keeps rank as one of the greatest books written by an American.

R.C. Reed once wrote of him (Jonathan Edwards [1904]):

He thought as we still think on the great doctrines of grace, being a zealous Calvinist, and was in accord with the Presbyterian Church in his views of government, though he lived and wrought and died in the Congregational Church. If, therefore, any class of persons should honor the name and cherish the memory of Edwards, those should do so who hold Calvinistic views of doctrine, and Presbyterian principles of polity.

Samuel Miller explains why we remember such a man as Jonathan Edwards (Lives of Jonathan Edwards and David Brainerd [1837]):

We owe to the dead themselves the duty of commemorating their actions, of cherishing their reputation, and of perpetuating, as far as possible, the benefits which they have conferred upon us.

As we likewise cherish the legacy of those great men and women who have gone before us and whose contributions to the kingdom of God on earth have left such an enduring mark, Jonathan Edwards stands out among the roll call of the saints, and it is with pleasure, and with thanks to God, that we take time today to honor his memory.

J.R. Miller: A Brief Remembrance

Receive our blog posts in your email by filling out the form at the bottom of this page.

It was said of J.R. Miller, the Presbyterian minister and devotional writer that “he kept a complete record of all the important dates in the lives of his people — birthdays, wedding anniversaries, et cetera — and he marked each of these by sending a short letter of remembrance” (J.T. Faris, The Life of Dr. J. R. Miller: "Jesus and I are Friends” [1912], p. 168).

At Log College Press, we too try to remember the important dates in the lives of “our people,” those men and women from the past whose lives and writings continue to live on and touch our readers today. Today we remember J.R. Miller who was born on this day in history, March 20, 1840.

He was born in Beaver County, Pennsylvania and raised in a Presbyterian home where he was taught Scripture, the Shorter Catechism and Matthew Henry’s Bible commentary, while family worship was practiced daily. His profession of faith was made in an Associate Presbyterian church in 1857, which became part of the United Presbyterian Church (UPCNA) a year later.

During the War Between the States he served in the U.S. Christian Commission from 1863 to 1865. He studied at Westminster College and at Allegheny Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania before entering the ministry and becoming ordained in the UPCNA in 1867. He later came to have scruples about the practice of exclusive psalmody to which his family and his church held. And thus he joined the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA), the denomination in which he remained for the rest of his life, just nine days after the Old and New School branches reunited in 1869.

In 1880, he began editorial work for the Presbyterian Board of Publication in Philadelphia, and he also published his first book, Week Day Religion. He would go on to write many more books, and numerous articles. He was extremely popular in his day for his devotional contributions to Christian literature. His biographer wrote in 1912 that copies of his published books had sold over 2 million copies.

Throughout his life and his careers as a pastor and an author, Miller reflected the values that were instilled in him and which were important to him. He loved the Lord Jesus Christ and as a consequence loved others well. A younger minister once asked him the secret of success in the ministry. He replied thus in a letter:

Cultivate love for Christ and then live for your work. It goes without saying that the supreme motive in every minister’s life should be the love of Christ. ‘The love of Christ strengtheneth me,’ was the keynote of St. Paul’s marvellous ministry. But this is not all. If a man is swayed by the love of Christ he must also have in his heart love for his fellow men. If I were to give you what I believe is one of the secrets of my own life, it is, that I have always loved people. I have had an intense desire all of my life to help people in every way; not merely to help them into the church, but to help them in their personal experiences, in their struggles and temptations, their quest for the best things in character. I have loved other people with an absorbing devotion. I have always felt that I should go anywhere, do any personal service, and help any individual, even the lowliest and the highest. The Master taught me this in the washing of His disciples’ feet, which showed His heart in being willing to do anything to serve His friends. If you want to have success as a winner of men, as a helper of people, as a pastor of little children, as the friend of the tempted and imperilled, you must love them and have a sincere desire to do them good (The Life of Dr. J. R. Miller: "Jesus and I are Friends,” pp. 87-88).

And this illustration speaks to the eternal truth of what Dr. Miller lived and practiced:

Love is never lost. Nothing that love does is ever forgotten. Long, long afterwards the poet found his song, from beginning to end, in the heart of a friend. Love shall find some day every song it has ever sung, sweetly treasured and singing yet in the hearts into which it was breathed. It is a pretty legend of the origin of the pearl which says that a star fell into the sea, and a shellfish, opening its mouth, received it, when the star became a pearl in the shell. The words of love’s greeting as we hurry by fall into our hearts, not to be lost, but to become pearls and to stay there forever (The Life of Dr. J. R. Miller: "Jesus and I are Friends,” pp. 204).

In his last days, while he was ill, the General Assembly of the PCUSA sent him a message of sympathy and encouragement. In fact, he himself was still working on The Book of Comfort when the end came and he entered into his eternal rest. J.R. Miller died on July 2, 1912, and was laid to rest at the West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania. A simple service was held for the occasion which included prayer, the recitation of the Twenty-Third Psalm, the singing by a soloist of “He Will Lead His Flock Like a Shepherd” from Handel’s Messiah, and the congregational singing of a favorite hymn.

Several of his books were devotionals meant to be read throughout the year. It seems fitting to conclude this brief remembrance of J.R. Miller with an extract from one of them, Dr. Miller's Year Book: A Year's Daily Readings (1895), from the very date of his birthday.

Davidson's Desiderata

Receive our blog posts in your email by filling out the form at the bottom of this page.

Early on in its history, in May 1853, a discourse was delivered at the Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania by Robert B. Davidson: Presbyterianism: Its True Place and Value in History (1854). After an overview of the history of Presbyterianism in Scotland and in early America, Davidson left his hearers with a list of things things desired or wanted in connection with the goal of preserving the history of Presbyterianism - a desiderata. This list was an inspired effort to steer the work of the Presbyterian Historical Society as it began to put into practice the vision of its founder, Cortlandt Van Rensselaer.

Collections of pamphlets, tractates, controversial and other essays, bearing on the history of the Presbyterian church in this country, especially touching the Schism of 1741. These should be bound in volumes, and arranged in chronological order, handy for reference. No time should be lost in this work, for pamphlets are very perishable commodities, and speedily vanish out of sight. A copy of Gilbert Tennent’s Remarks on the Protest cannot now be obtained. One was understood by Dr. Hodge, when he wrote his History, to be in the Antiquarian Library, in Worcester, Mass., but the work is reported by the librarian as missing. This shows us that we should hoard old pamphlets and papers with Mohammedan scrupulosity, especially when there are no duplicates.

Collections, like Gillies’, of accounts of Revivals, and other memoranda of the progress of vital religion. Such collections would be supplementary to Gillies’ great work, which does not embrace the wonderful events of the present century in America.

Collections of memoirs of particular congregations, of which quite a number have been at various times printed, and which ought to be brought together and preserved.

Collections of occasional Sermons, both of deceased and living divines. As old productions are of interest to us, so such as are of recent publication may interest posterity. Such collections would furnish good specimens of the Presbyterian pulpit, and might be either chronologically or alphabetically arranged.

Collections of discourses delivered about and after the era of the Revolution. They would exhibit in a striking and favorable light the patriotic sympathies of the clergy at that period, as also the popular sentiment on the independence of the States, and their subsequent union under the present constitution.

A similar collection of Discourses preached on the day of Thanksgiving in the year 1851, would be very interesting; exhibiting the various views held on the Higher Law, and the preservation of the Union, and also the value of the Pulpit in pouring oil on the strong passions of mankind.

Biographical sketches of leading Presbyterian divines and eminent laymen. It is understood that one of our most esteemed writers is engaged in the preparation of a work of this sort, embracing the different Christian denominations. Whatever emanates from his elegant pen will be sure to possess a standard value; but it is thought, from the very structure of his projected work, such a one as is now recommended will not interfere with it, nor its necessity be superseded. Mark the stirring catalogue that might be produced, names which, though they that bare them have been gathered to their fathers, still powerfully affect us by the recollection of what they once did, or said, or wrote, and by a multitude of interesting associations that rush into the memory: Makemie, the Tennents, Dickinson, Davies, Burr, Blair, the Finleys, Beattie, Brainerd, Witherspoon, Rodgers, Nisbet, Ewing, Sproat, the Caldwells, S. Stanhope Smith, John Blair Smith, McWhorter, Griffin, Green, Blythe, J.P. Campbell, Boudinot, J.P. Wilson, Joshua L. Wilson, Hoge, Speece, Graham, Mason, Alexander, Miller, John Holt Rice, John Breckinridge, Nevins, Wirt. Here is an array of names which we need not blush to see adorning a Biographia Presbyterianiana. And the materials for most of the sketches are prepared to our hand, and only require the touch of a skilful compiler.

Lives of the Moderators. There have been sixty-four Moderators of the General Assembly; and as it is usual to call to the Chair of that venerable body men who enjoy some consideration among their brethren, it is fair to infer that a neat volume might be produced. Many were men of mark; and where this was not the case, materials could be gathered from the times in which they lived, or the doings of the Assembly over which they presided.

A connected account or gazetteer of Presbyterian Missions, both Foreign and Domestic, with sketches of prominent missionaries, and topographical notices of the stations. Dr. Green prepared something of this sort, but it is meagre, and might be greatly enlarged and enriched.

Reprints of scarce and valuable works. It may be objected that we have already a Board of Publication, who have this duty in charge; but it is not intended to do anything that would look like interference with that useful organ. The Board are expected to publish works of general utility, and likely to be popular, and so reimburse the outlay; this society would only undertake what would not fall strictly within the Board’s appropriate province, or would interest not the public generally, but the clerical profession.

A continuation of the Constitutional History of the Presbyterian Church to the present time. The valuable work of Dr. Hodge is unfinished; and whether his engrossing professional duties will ever allow him sufficient leisure to complete it is, to say the least, doubtful.

Should that not be done, then it will be desirable to have prepared an authentic narrative of the late Schism of 1838; or materials should be collected to facilitate its preparation hereafter, when it can be done more impartially than at present. Dr. Robert J. Breckinridge did a good service in this way, by publishing a series of Memoirs to serve for a future history, in the Baltimore Religious and Literary Magazine.

It might be well to compile a cheap and portable manual for the use of the laity, containing a compact history of the Presbyterian Church in America.

Other proposals on Davidson’s list include a history of the rise and decline of English Presbyterianism; a history of the French Huguenots; and a history of the Reformation in Scotland as well as biographical sketches of Scottish divines.

It is a useful exercise for those who share Davidson’s interest in church history to pause and reflect on the extent to which the goals that he proposed have been met. The Presbyterian Historical Society itself — located in Philadelphia — has certainly done tremendous legwork in this regard as a repository of valuable historical materials which has allowed scholars the opportunity to study and learn from the past. We are extremely grateful for the efforts of the Presbyterian Historical Society. Samuel Mills Tenney’s similar vision led to the creation of the Historical Foundation of the Presbyterian and Reformed Churches in Montreat, North Carolina. The PCA Historical Center in St. Louis, Missouri is another such agency that has done great service to the church at large as a repository of Reformed literature and memorabilia.

We do have access today to Gilbert Tennent’s Remarks Upon a Protestation Presented to the Synod of Philadelphia, June 1, 1741. By 1861, we know that a copy was located and deposited, in fact, at Presbyterian Historical Society. Though not yet available in PDF form at Log College Press, it is available for all to read online in html through the Evans Early American Imprint Collection here.

The biographical sketches then in progress that Davidson referenced in point #7 were carried through to publication by William B. Sprague. His Annals of the American Pulpit remain to this day a tremendous resource for students of history, yet, as Davidson wisely noted, though many writers have followed in Sprague’s footsteps on a much more limited basis, there is always room for more to be done towards the creation of a Biographia Presbyterianiana.

Regarding the Lives of Moderators (point #8), we are grateful for the labors of Barry Waugh of Presbyterians of the Past to highlight the men that Davidson had in mind. The lists and biographical sketches that he has generated are a very useful starting point towards achieving the goal articulated by Davidson, and help to bring to mind the contributions of Moderators to the work of the church.

There are a number of organizations that have taken pains to reprint older Presbyterian works of interest. Too many to list here, the contributions of all those who share this vision to make literature from the past accessible to present-day readers is to be applauded, including the efforts of Internet Archive, Google Books and others who digitize such works. We at Log College Press also strive to do this both with respect to reprints and our library of primary sources. For us, the past is not dead, primary sources are not inaccessible, and the writings of 18th-19th century Presbyterians are not irrelevant. It is worth noting that there are topical pages with growing resources available on Log College Press that highlight material on biographies, church history, the 1837 Old School / New School division, sermons and much more.

Much more could be said in regards to the extent to which organizations, historians and others have carried forward the goals articulated by Davidson. But for now we leave it to our readers to consider Davidson’s Desiderata, articulated over 150 years ago, and its connection to our shared interest in preserving the history and literature of early American Presbyterianism.

Three Wrights at Log College Press

Receive our blog posts in your email by filling out the form at the bottom of this page.

Three years ago we introduced to our readers the famous 19th century author, Mrs. Julia McNair Wright (1840-1903), who penned numerous biographical sketches and works of fiction, primarily aimed at younger readers. Today, on his birthday, we introduce her husband, the also noteworthy Rev. Dr. W.J. Wright (August 3, 1831-February 26, 1903).

Born at Weybridge, Vermont, the latter Wright graduated from Union College in Schenectady, New York in 1857. After a brief period spent teaching and in the practice of law, he pursued theological studies, first at Union Theological Seminary (New York), and then at Princeton Theological Seminary, graduated from there in 1862. From 1863-1865, he served as a chaplain in the U.S. Army. Except for a two-year period spent studying in Europe (1871-1873), he served as pastor of several congregations in New Jersey, Ohio and West Virginia. Briefly, he served as professor of mathematics at the Wilson Female College in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania (1876-1877), but more significantly, he served as the chair of metaphysics and as vice-president at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri (1887-1899). Author of several tracts of mathematics, he was the first American admitted to the London Mathematical Society. Like his wife, he was a contributor to The Presbyterian Quarterly, including one article on the powerful but unBiblical legacy of Darwinism, a generation after the hypothesis was first proposed.

Married in 1859 to his bride, it was Julia McNair Wright who became a 19th century household name, rather than her husband. It was in that year that Mrs. Wright published her first story, beginning a long and successful career as an author of so many works of a biographical, fictional, Biblical and scientific nature. Her pen was particularly active in the late 1860s and early 1870s, when numerous articles and stories appeared in the press, including two sets of 12 volumes each: True Story Library No. 1 and No. 2. She often focused on the temperance cause, or on anti-Catholic stories, but the diverse range of her interests was tremendous, and included some translation work. Her particular forte was in writing to young readers to stimulate minds and hearts for service to God. She often wrote for Presbyterian periodicals, as well as for the Presbyterian Board of Publication.

Together they had two children, who survived their parents after both passed away in the same year: a son, John M. Wright, of New York City, and a daughter, Jessie Elvira Wright Whitcomb, of Kansas City, Missouri. Jessie, born at Princeton, New Jersey, also became known as both a writer and a lawyer. She was a member of the Presbyterian church, like her parents. She and her husband, George Herbert Whitcomb, were classmates at Boston University Law School, and later became partners at George’s law firm. He also served as a judge and a professor of law. They had six children, several of whom were also noted in their fields.

B.B. Warfield had occasion to review some of the writings of both Julia and Jessie over the years, and gave them high commendation. All three Wrights highlighted here used their gifts for the service of others, and as authors left a legacy that still enriches readers over a century later. The Wrights are worth getting to know.

Halsey's Notable Women of Christianity

Receive our blog posts in your email by filling out the form at the bottom of this page.

Writing for the journal Our Monthly in 1870-71, Prof. Leroy J. Halsey of McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago provided readers with a set of biographical sketches of Notable Women of Christianity. The six sketches include:

Helena, the Mother of Constantine — Halsey makes the case that Roman Empress Helena (d. 330 AD) was a Christian believer and spiritually influenced her son Constantine the Great before and after his conversion, contrary to the account of Eusebius that she was only converted after Constantine.

Vittoria Colonna - Colonna (1492-1547) was an Italian noblewoman and poet, who, as Halsey notes, evidenced “Calvinistic” views in her poetry. She is said also to have been both a muse and spiritual guide to Michelangelo.

Marguerite of Navarre - Marguerite (1492-1549) was a Princess of France and Queen of Navarre. She was highly educated and a gifted poet, and, though she ever officially left the Church of Rome, she did what she could to support the Reformation, and corresponded often with John Calvin.

Olympia Fulvio Morata - Morata (1526-1555) was an Italian scholar who was a friend to Vittoria Colonna, Marguerite of Navarre, John Calvin and others in Protestant circles. Indeed, she lectured on the works of Calvin. The account of her faith on her deathbed (she was stricken down at the age of 29 by the plague) given by Halsey is very moving.

Lady Huntingdon - Selina Hastings (née Shirley), Countess of Huntingdon (1707-1791) was an English lady prominent in the Methodist movement. She served as principal of Trevecca College, Wales and did much to support the work of the Methodist Church financially and otherwise.

Hannah More - More (1745-1833) was an English poet, playwright and philanthropist who was moved by her Christian faith to act on behalf of the poor and oppressed. Halsey writes of her life of service, and her world-wide influence (she was visited by William B. Sprague on one of his tours of the continent as noted in Visits to European Celebrities (1855)).

In this series of sketches, Halsey aimed to highlight not only noble women but the nobility of women. The virtues of education, love and, above all, faith are the characteristics which stand out in Halsey’s biographies. Take note of these Christian women through the centuries, and their stories, which speak to us yet today.

Celebrating Thomas E. Peck's 200th Birthday

Receive our blog posts in your email by filling out the form at the bottom of this page.

It was 200 years ago today that Thomas Ephraim Peck was born in Columbia, South Carolina on January 29, 1822. Clement Read Vaughan’s biographical sketch, found on his page on Log College Press and in Vol. 3 of Peck’s Miscellanies, edited by Thomas Cary Johnson, tells the story of his life (take note also of Iain H. Murray’s sketch in Vol. 1 of the same, as republished by Banner of Truth in 1999).

After training for the ministry at Columbia Theological Seminary, Peck served pastorates in Baltimore, Maryland, and collaborated with Stuart Robinson in an editorial capacity, before spending the final 33 years of his life as a professor at Union Theological Seminary in Virginia. His preaching was highly regarded and his literary endeavors show him to be a man great intellect and deep spirituality. He died on October 2, 1893, and his body was laid to rest in the Union Theological Seminary Cemetery, Hampden Sydney, Virginia.

Peck was truly notable leader in the 19th century Presbyterian church, whose life and ministry are to be remembered on this bicentennial anniversary of his birth. Vaughan said of him, “As an expositor of truth, as an exegete of Scripture, as a philosophic student of history, he was probably without a rival in his day.” Read his works online here, and get to know Thomas E. Peck, a Southern Presbyterian worthy.

Nevin's Presbyterian Encyclopedia

(Receive our blog posts in your email by clicking here. If the author links in this post are broken, please visit our Free PDF Library and click on the author’s page directly.)

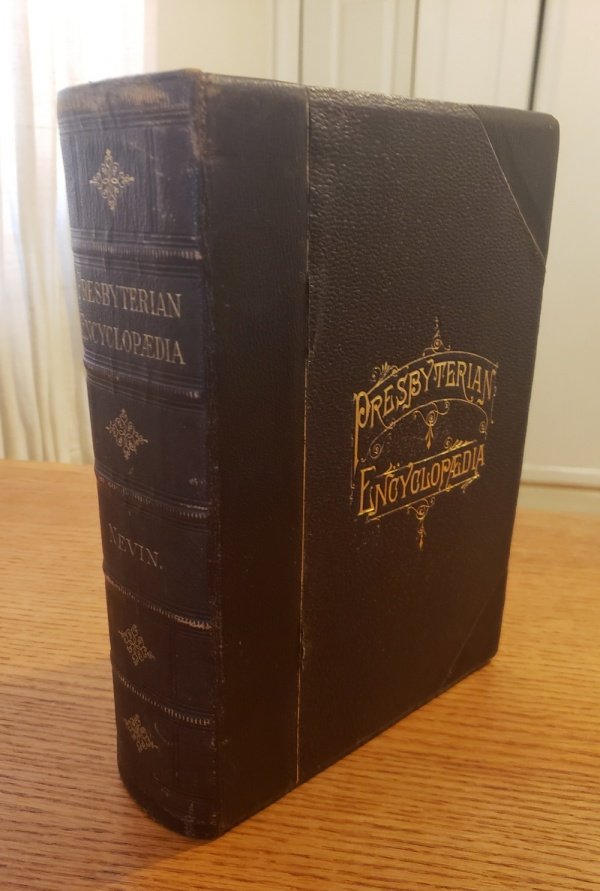

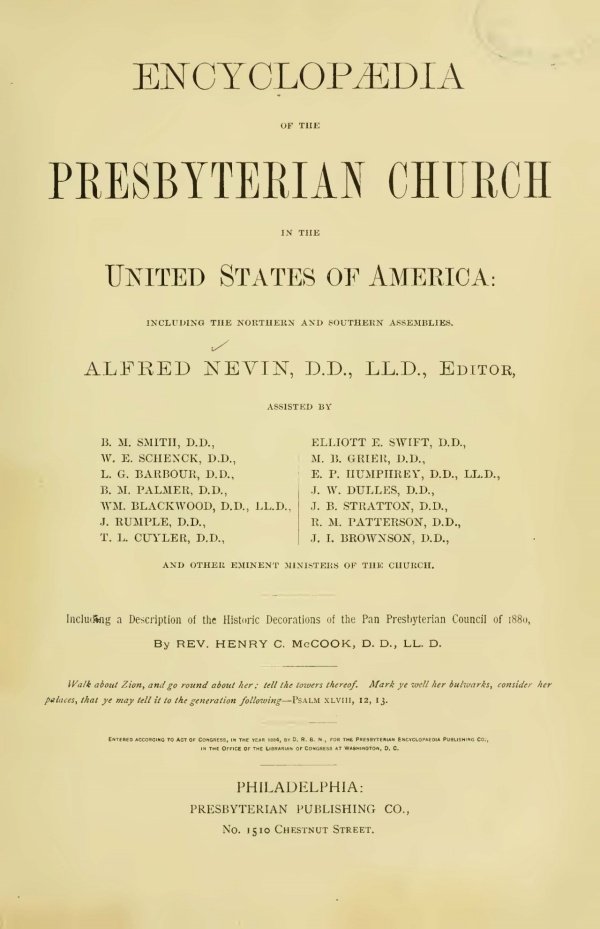

There are some wonderful modern dictionaries and encyclopedias of Presbyterianism (D.G. Hart & Mark Knoll’s Dictionary of the Presbyterian and Reformed Tradition in America [2005], and Donald K. McKim’s Encyclopedia of the Reformed Faith [1992] come to mind). But in this writer’s view, though somewhat limited in usefulness to the modern student of church history by its late 19th century date of publication, still nothing compares to the magnificent Encyclopedia of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, Including the Northern and Southern Assemblies (1884) by Alfred Nevin.

Alfred Nevin’s Presbyterian Encyclopedia.

It is a treasure that spans over 1,200 pages, and includes many illustrations, and also Henry C. McCook’s Historic Decorations at the Pan-Presbyterian Council: A Lithographic Souvenir, a collection of beautiful tributes to the people and places of the First and Second Reformations which were a highlight of the 1880 Pan-Presbyterian Council. The Encyclopedia itself is full of biographical sketches of noted Presbyterian ministers, and articles on different aspects of church history, in rich detail.

Noted contributors to Nevin’s Presbyterian Encyclopedia include B.B. Warfield, Charles A. Stillman, A.A. Hodge, James C. Moffat, W.A. Scott, Sheldon Jackson, Henry Van Dyke, Sr., J. Aspinwall Hodge and others.

Title page.

We at Log College Press often return to this volume as we work to expand our knowledge of American Presbyterianism and make accessible the men and women and their writings which are reflected therein to all. Take note of this remarkable resource for your own studies of church history and biography, which is available to read online at the Alfred Nevin page.

An American Presbyterian Missionary Who Was Knighted by an English King

(Receive our blog posts in your email by clicking here. If the author links in this post are broken, please visit our Free PDF Library and click on the author’s page directly.)

It is not every day that one finds an American Presbyterian minister who was knighted by a British monarch. Billy Graham comes to mind — he was awarded an honorary knighthood by Queen Elizabeth II in 2001. But the subject of today’s post was knighted by King George V on January 1, 1923.

The reason for such an honor in the case of Sir James Caruthers Rhea Ewing (1854-1923) was to acknowledge Ewing’s 43 years of service as a missionary in what was then British-controlled India. King George at that time was not only king of the United Kingdom and British dominions, but also Emperor of India.

Ewing had previously been titled Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire in 1915, but in 1923, he gained the title of Honourary Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire and was henceforth known as “Sir James.”

A graduate of Washington & Jefferson College in Western Pennsylvania, Ewing went on to serve in the missionary field, but also as Vice-Chancellor of the University of the Punjab and as President of the Forman Christian College. An educator as well as a missionary, Ewing labored many decades for the cause of Christ to shine a bright light in a dark place.

Read more about his life story in the biography by Robert E. Speer: Sir James Ewing, For Forty-Three Years a Missionary in India: A Biography of Sir James C.R. Ewing, M.A., D.D., LL.D., Litt.D. C.I.E, K.C.I.E. (1928).

Forgotten Founding Fathers of the American Church and State

(Receive our blog posts in your email by clicking here. If the author links in this post are broken, please visit our Free PDF Library and click on the author’s page directly.)

There is a volume of biographical sketches that is well worth the read - William T. Hanzsche’s Forgotten Founding Fathers of the American Church and State (1954). It highlights some of the most significant colonial Presbyterians found on Log College Press. These include: Francis Makemie (“the Father of American Presbyterianism”); William Tennent, Sr. (founder of the Log College); Jonathan Dickinson (first President of the College of New Jersey in Princeton); David Brainerd (the “Apostle to the North American Indians”); Gilbert Tennent (“Son of Thunder”); Samuel Davies (the “Apostle to Virginia”); and John Witherspoon (the only clergyman to sign the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation).

Hanzsche’s study is a great introduction to these men and their legacies. Their contributions to early American Presbyterianism, and indeed, to the history of the United States and the world, are worthy of notice and appreciation. This volume helps students of history to better understand the significance of each of these American Presbyterian worthies.

John Moorhead: Pastor of Boston's Church of the Presbyterian Strangers

(Receive our blog posts in your email by clicking here. If the author links in this post are broken, please visit our Free PDF Library and click on the author’s page directly.)

In the midst of the great Puritan Migration to New England (1620-1640), some Scotch-Irish assembled a congregation in Boston, Massachusetts which was known as the ‘Church of the Presbyterian Strangers.’ Its first pastor was the Rev. John Moorhead (1703-1773). He was born in Newton, near Belfast, in County Down, Ireland (Ulster), and educated in Edinburgh, before arriving in Massachusetts.

All accounts indicate that he was a very pious minister, who engaged in family visitation, catechism, and a faithful ministry of the Word. He left a deep impression among his flock and others, and has been noted in various studies of New England Presbyterianism.

It was not until 1730 that a Presbyterian Church was organized in Boston. Under the leadership of the Reverend John Moorhead a congregation known as “The Church of the Presbyterian Strangers” was organized and met in a “converted barn” owned by John Little on Long Lane. In 1735 title to the property was conveyed to the congregation for use by the Presbyterian Society forever “and for no other use, intention, or purpose whatever.” This “converted barn” served the congregation until 1744 when a new edifice was erected. It was in this building in 1788 that action was taken to make Massachusetts a state, in commemoration of which the name Long Lane was changed to Federal Street and the meeting house came to be known as Federal Street Church.

The congregation flourished and by the time their new building was erected numbered more than 250. Mr. Moorhead served the group until his death in December, 1773, following which the church was supplied by itinerant ministers [including David McClure] until 1783 when the Reverend Robert Annan was called to be pastor. Internal strife and opposition from the Puritan oligarchy finally led Mr. Annan to resign in 1786 after which the group voted themselves into a Congregational Society and after 1803 when William Ellery Channing became pastor, they joined the Unitarian fold. Relocating and erecting a new building in 1860 this group became the Arlington Street Church. In similar fashion one by one most of the seventy fairly well established Presbyterian churches of eighteenth century New England went over to other denominations. — Charles N. Pickell, Presbyterianism in New England: The Story of a Mission, pp. 6-7

A memoir of Moorhead written in 1807 says this of the early days of that congregation:

This little colony of Christians, for some time, carried on the public worship of God in a barn, which stood on the lot which they had purchased. In this humble temple, with uplifted hearts and voices, they worshipped and honoured Him, who, for our salvation, condescended to be born in a stable.

This same biographer highlights an important aspect of Moorhead’s ministry - family visitation.

Once or twice in the year, Mr. Moorhead visited all the families of his congregation, in town and country; (one of the Elders, in rotation, accompanying him,) for the purpose of religious instruction. On these occasions, he addressed the heads of families with freedom and affection, and inquired into their spiritual state, catechised and exhorted the children and servants, and concluded his visit with prayer. In this last solemn act, (which he always performed on his knees, at home and in the houses of his people), he used earnestly to pray for the family, and the spiritual circumstances of each member, as they respectively needed.

In addition to this labour of family visitations, he also convened, twice in the year, the families, according to the districts, at the meeting-house, when he conversed with the heads of families, asking them questions, on some of the most important doctrines of the gospel, agreeably to the Westminster confession of faith; and catechised the children and youth.

A young parishioner of Rev. Moorhead, David McClure, who briefly ministered to the flock in Boston after Moorhead’s death, wrote in his journal about this feature of the ministry at the Church of the Presbyterian Strangers.

We had the special advantage of a religious education & government in early life. Our parents gave us the best school education that their circumstances would allow. The children who could walk were obliged to attend public worship on the Sabbath, & spend the interval in learning the Shorter & the Larger Westminster Catechisms, & committing to memory some portion of the Scriptures. My mother commonly heard us repeat the catechisms on Sunday evenings. My parents departed with the supporting hope of salvation through the glorious Redeemer. In her expiring moments my mother gave her blessing & her prayers to each of her children, in order. She had many friends who mourned her death. She was favored with a good degree of health & was very cheerful, active & laborious, in the arduous task of raising, with slender means, a large family. To the labours of our worthy minister the Rev. Mr. Moorhead, we were much indebted for early impressions of religious sentiments. His practice was frequently to catechize the Children & youth at the meeting House & at their homes & converse & pray with them. He also visited & catechized the heads of all the families in his congregation, statedly.

Moorhead is mentioned often in Alexander Blaikie’s History of Presbyterianism in New England (although under the spelling of “Moorehead”). Blaikie writes that Moorhead was ordained on March 30, 1730, and adds that

"This religious society was established by his pious zeal and assiduity."…He was the forty-sixth minister settled in Boston, and "soon after his induction he married Miss Sarah Parsons, an English lady, who survived him about one year."

André Le Mercier, the 37th minister settled in Boston, a French Huguenot Presbyterian, was a colleague of Moorhead’s at this time and is mentioned by Blaikie in this connection.

A letter from Rev. Moorhead [not yet available on Log College Press] was published in Glasgow, Scotland in 1741, which gives an account of conversions associated with the Great Awakening ministries of George Whitefield and Gilbert Tennent.

Portrait of Phillis Wheatley by Scipio Moorhead (1773). It is said to be “the first frontispiece depicting a woman writer in American history, and possibly the first ever portrait of an American woman in the act of writing.”

Moorhead was a slave owner. His slave, Scipio Moorhead, is famous in history for his artistic skill. His portrait of Phillis Wheatley appeared in her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773). Wheatley wrote An Elegy to Miss Mary Moorhead, on the Death of Her Father, the Rev. Mr. John Moorhead in December 1773. Of him she wrote:

With humble Gratitude he render'd Praise,

To Him whose Spirit had inspir'd his Lays;

To Him whose Guidance gave his Words to flow,

Divine Instruction, and the Balm of Wo:

To you his Offspring, and his Church, be given,

A triple Portion of his Thirst for Heaven;

Such was the Prophet; we the Stroke deplore,

Which let's us hear his warning Voice no more.

But cease complaining, hush each murm'ring Tongue,

Pursue the Example which inspires my Song.

Let his Example in your Conduct shine;

Own the afflicting Providence, divine;

So shall bright Periods grace your joyful Days,

And heavenly Anthems swell your Songs of Praise.

The “Presbyterian Strangers” of Boston thought very highly of their pastor. In his funeral sermon [not yet available on Log College Press], by David McGregore, he was described as “an Israelite indeed.” He left an enduring legacy that is reflected in the lives of David McClure and others. Boston is not the city set upon a hill that it once was, although pockets of piety endure. But Moorhead is worthy of remembrance today as a pioneer of New England Presbyterianism.

The Man, Charles Hodge

(Receive our blog posts in your email by clicking here. If the author links in this post are broken, please visit our Free PDF Library and click on the author’s page directly.)

Editorial note: This is the first in a planned series of articles by Rev. Dylan Rowland, Pastor of Covenant Orthodox Presbyterian Church (OPC) in Mansfield, Ohio, about the life and legacy of Dr. Charles Hodge.

Charles Hodge (1797-1878) was an American Presbyterian theologian and prolific theological commentator. Some have even gone so far as to refer to Hodge as being the so-called, “Pride of Princeton,” and this not without good reason [1]. Having studied theology at Princeton Seminary and graduating in 1819, Hodge was soon called to be the third professor at the seminary along with Presbyterian luminaries such as Archibald Alexander and Samuel Miller. There, Hodge began what would become more than 50 years of educating and preparing men for Christian ministry. During his theological career, Hodge produced a variety of works including his popular The Way of Life, numerous articles for The Biblical Repertory and Princeton Review, his three-volume systematic theology, and much more. Due to his theological vigor, Hodge is recognized by many as being one of the most important American Presbyterian theologians of the nineteenth century.

However, it ought not merely be Hodge’s academic prowess which awards him this status, but also the quality of person he was. I contend that Hodge is worth spending hours reading, not only because of his intellectual brilliance, but also because of the man himself. Hence, this article is the first of many exploring the personal life of Charles Hodge. In studying Hodge’s personal life, readers will find what kind of man God had raised up to teach subsequent generations of pastors and theologians. Prayerfully, a study concerning Hodge’s personal life will demonstrate to a greater degree the value of Hodge’s theological ministry at Princeton Seminary.

To begin this study, it is necessary to begin at the end, after Hodge had gone to be with the Lord. The following is a testimonial concerning the life and work of Hodge printed in the National Repository, a Methodist magazine. The editor’s words set the stage for understanding better Charles Hodge, the man:

Timothy Dwight, Nathaniel Emmons, Samuel Hopkins, Edwards A. Park, Moses Stuart, Nathaniel W. Taylor, Albert Barnes, the Alexanders, Francis Wayland, Tayler Lewis, Bishop McIlvaine, Bangs, Fisk, McClintock, Whedon, Bledsoe, Dr. True, whose loss we have just been called on to mourn also, and a hundred others have shed lustre on the American name since the era of independence opened; but none of these can, in grandeur of achievement, compare with Charles Hodge, who recently died at Princeton, an octogenarian. He was not only par excellence the Calvinistic theologian of America, but the Nestor of all American theology, and though we differ widely with him in many things, we yet accept this master mind and beautifully adorned life as the grandest result of our Christian intellectual development. He produced many valuable writings, but above all stands his ‘Systematic Theology,’ a work which has only begun its influence in moulding the religious thought of the English-speaking world. We could wish that its fallacy of dependence on the Calvinistic theology were not one of its faults. But what is this slight failing compared to the masterful leading of a thousand, lost in speculation, from the labyrinth of doubt and despair to the haven of heavenly faith and angelic security? We may say of this now sainted man, ‘With all thy faults we love thee still.’ Princeton has lost its greatest ornament, the Presbyterian Church its most precious gem, the American Church her greatest earth-born luminary [2].

[1] See the insightful biography of Charles Hodge written by W. Andrew Hoffecker, Charles Hodge: The Pride of Princeton (2011, Phillipsburg, New Jersey: P&R Publishing).

[2] A.A. Hodge, The Life of Charles Hodge D.D. LL.D. (1880), pp. 585-586.

Judith G. Perkins: The Flower of Persia

(Receive our blog posts in your email by clicking here. If the author links in this post are broken, please visit our Free PDF Library and click on the author’s page directly.)

Although we have previously highlighted the letter of 10 year-old A.A. Hodge and his younger sister Mary Elizabeth to the “heathen” of India, both went on to live full lives on earth to the glory of God. Today we highlight a young lady who lived her full life on earth to the ripe age of twelve years old.

Judith Grant Perkins was the daughter of Justin and Charlotte Perkins, missionaries to Persia, the fourth of seven children in the family. Her biography was primarily authored by Joseph Gallup Cochran: The Persian Flower: A Memoir of Judith Grant Perkins of Oroomiah, Persia (1853). Judith was born on August 8, 1840 at Urmia, Persia (now Iran).

She visited America once as a child. The story of that journey is found in Justin Perkins, A Residence of Eight Years in Persia, Among the Nestorian Christians (1843). But otherwise, she lived in Persia the rest of her life.

Judith was a precocious girl, who learned to read and write very well (her biography includes a number of letters that she wrote, and Log College Press has one letter in her own hand — written at the age of eight — which shows her excellent penmanship). She was interested in music, an avid reader (one of the last books she read — out loud to her mother — was Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin), and she assisted her father in his translation labors. She had a heart for advancing the gospel in other parts of the world, even thinking of one day laboring in China as a missionary.

Judith's interest in the cause of missions, was of early growth. When quite a small child, she often spoke of becoming a missionary, and was then particularly interested in China, as a prospective field of labor. And to the last, she always seemed to assume, that she should be a missionary somewhere, if her life were spared. Reading the memoirs of female missionaries, as the memoir of Harriet Newell, and that of Mrs. Dwight and Mrs. Grant, and of Mrs. Van Lennep, and others, served to quicken that desire, and strengthen that impression; and her circumstances on missionary ground, naturally kept the subject fresh before her mind. She said to some of the older Nestorian girls of the seminary, the last time she ever saw them, and only four days before her death, "I hope, after I return from Erzroom, to study very hard, and afterward go to America, and attend school awhile there, and then return and be a missionary here; or, I would prefer to go and labor where there are no missionaries."

In an important sense, Judith had long been a missionary helper. She ever manifested a very deep interest in all the departments of the good work among the Nestorians, and sought to aid in its progress in every way in her power. She had sat patiently many an hour, and assisted her father in adjusting the verses of the translation of the Bible according to the English version; reading the latter verse by verse; and she seldom seemed happier than when aiding him in that great work, which she longed to see accomplished. During the last year of her life, she assisted her mother in teaching a few Nestorian females connected with the Sabbath school, and .eagerly engaged in the loved employment.

It was while traveling with her family that she was stricken with illness. While lingering like the fragile flower she was, her father later recounted a conversation with Judith that reveals her inner spirit.

Once when I asked her, 'Dear Judith, is Jesus precious to you?' ‘O yes,' she replied; 'I have just had a view of Him; O how lovely!' What a balm was that reply to our writhing hearts! At another time, I inquired, 'Dear Judith, have you a desire to get well?' She replied, 'O, yes, papa, if it be God's will.' 'Why, dear Judith?' I inquired. '‘That I may do good,' she answered. ‘And if it is His will to take you now to Himself, are you not satisfied?' I inquired. 'O yes, papa; His will be done,' was her reply.

Towards the end, her father records a prayer that she uttered:

About this time, her papa and mamma kneeled over her and prayed in succession. She remained silent a few moments after we closed; and then, without any suggestion from us, uttered the following short prayer, slowly and distinctly, and evidently from the depths of her soul — 'O Lord, accept me; if it be thy will, make me well again; if not, oh let me not murmur.' We responded an audible amen.

She died of cholera on September 4, 1852 at the age of twelve, and was buried at the American Mission Graveyard outside of Urmia, where it is reported of the 60 or so individuals interred there, around 40 are children.

Her witness to the grace of Jesus Christ, who worked in her and through her, touched the lives of those who knew her, and many others who have read her life story over the years. We remember her as a flower who grew in Persia, and was transplanted to a more a beautiful garden above.

Happy birthday to John T. Faris!

(Receive our blog posts in your email by clicking here. If the author links in this post are broken, please visit our Free PDF Library and click on the author’s page directly.)

Editor, author, traveler and Presbyterian minister, John Thomson Faris was born 150 years ago today on January 23, 1871 at Cape Girardeau, Missouri. John studied at several schools, including Princeton and McCormick Theological Seminary. His father, William Wallace Faris, was both a Presbyterian minister and an editor, in whose footsteps, in both capacities, John would follow. John’s brother, Paul Patton Faris, also became a minister and an author.

In the field of journalistic publishing, John worked for The Talk, Anna, Illinois (1890); The Occident, San Francisco, (1891–1892); and The North and West, Minneapolis (1892). Ordained to the ministry in 1898, John ministered in Mt. Carmel, Illinois and St. Louis, Missouri, before taking on official journalistic duties for the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA). He saw the importance of Sunday School, and this would become a focus of his labors.

He served as editor of the Sunday School Times, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1907–1908); and editor of the Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath School Work, Philadelphia (1908–1923). He was the Director, Editorial division, of the Board of Christian Education of the PCUSA (1923–1937). Finally, he served as General Director of the editorial department of the Presbyterian Board of Christian Education, and as President of the Sunday School Council of the Evangelical Denominations.

He had a special affinity for J.R. Miller, whose biography he authored, and several of whose works he posthumously edited and published.

John T. Faris traveled extensively, and wrote prolifically. He published over 60 books, many of which highlighted the history and the geography of America. He focused on the romance of the past, and the virtues needed for the present, as well as the value of Sunday School for the strengthening the work of the kingdom. He seemed to have a vision for reaching people through words and imagery that evoked the best virtues in his readers. He died on April 13, 1949, and is buried in the same cemetery at Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania as where J.R. Miller is interred. We continue to add Faris’ writings to Log College Press, but today we remember that while his mortal life began 150 years ago, his legacy through the written word endures.

Writing on the Sand: Verse by John Hall

(Receive our blog posts in your email by clicking here. If the author links in this post are broken, please visit our Free PDF Library and click on the author’s page directly.)

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time. — Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “A Psalm of Life”

Christian biographies are a treasure that will enrich the reader who seeks them out. The lives of saints who have gone before us can teach us much not only about those men and women, but about how God works from generation to generation, even our own.

Recently added to Log College Press is Thomas Cuming Hall’s life story of his father, John Hall, Pastor and Preacher: A Biography (1901). John Hall (1829-1898) was born in County Armagh, Ireland. After laboring as a missionary and pastor in Ireland, he attended the 1867 PCUSA General Assembly meeting as a delegate, and was soon thereafter called to minister to the Fifth Street Presbyterian Church in New York City, where he would serve for the remainder of his life. He survived an assassination attempt by a deranged shooter in 1891.

From his biography, we take note of the many poems he composed over the years. One in particular stands out, which evokes perhaps to the modern reader thoughts of a famous 20th century poem known as “Footprints in the Sand.” But these lines were written by Hall in 1858, and thanks to their publication in The Missionary Herald that year, and the notice given to them in his biography, these lines have not “washed away”; we recall them to mind today.

WRITING ON THE SAND

Alone I walk'd the ocean strand—

A pearly shell was in my hand;

I stoop'd, and wrote upon the sand

My name—the year—the day.

As onward from the spot I pass'd

One lingering look behind I cast.

A wave came rolling high and fast,

And wash'd my lines away.And so, methought, 'twill shortly be

With every mark on earth from me;

A wave of dark oblivion's sea

Will sweep across the place.

Where I have trod the sandy shore