(If the author links in this post are broken, please visit our Free PDF Library and click on the author’s page directly.)

They say that the candle that burns brightest, burns half as long. Church history has many examples to offer in support of this truism. For example, consider the following, to name a few:

Lady Jane Grey, English Queen (1536/1537 - 1554, age 16/17)

Andrew Gray, Scottish Puritan (1634 – 1656, age 22)

Patrick Hamilton, Scottish Reformer (1503 – 1528, age 24)

James Renwick, Scottish Covenanter (1662 – 1688, age 26)

Jim Elliot, American Missionary (1927 – 1956, age 29)

Robert Murray M’Cheyne, Scottish Presbyterian (1813 – 1843, age 29)

David Brainerd, American Presbyterian Missionary (1718 – 1747, age 29)

Christopher Love, English Presbyterian (1618 – 1651, age 33)

James Durham, Scottish Presbyterian (1622 – 1658, age 36)

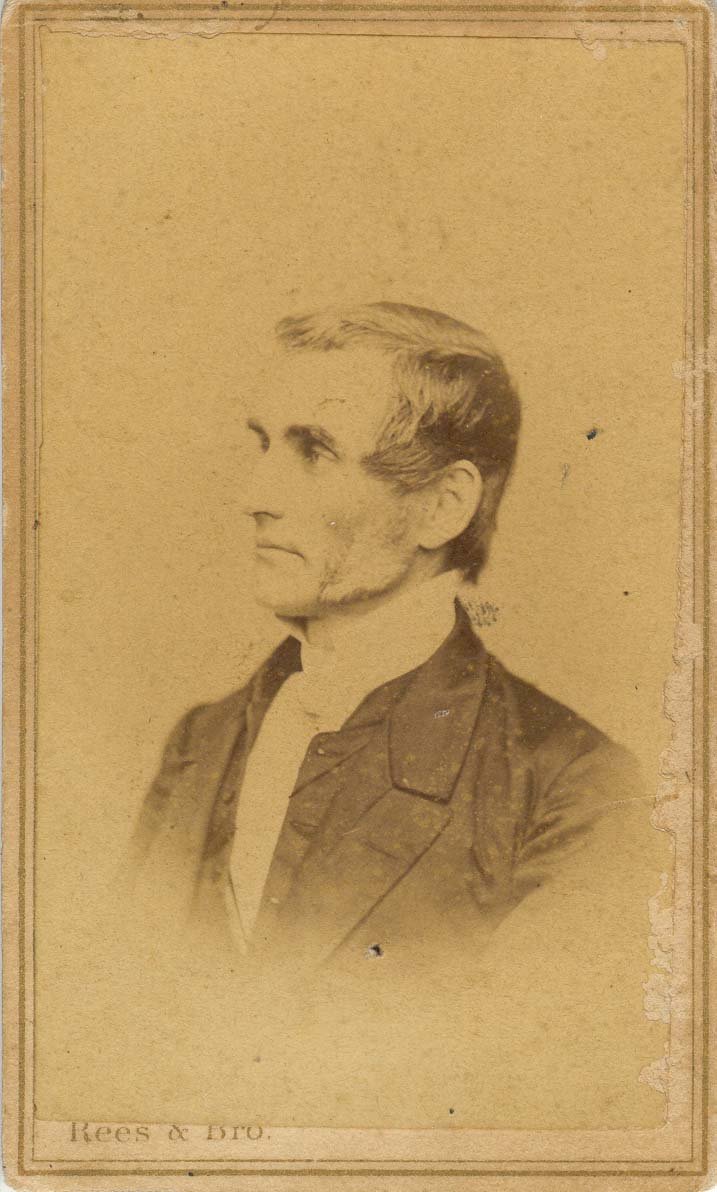

There is another name to add to this distinguished list, one that is less well-known, but equally as inspirational as the names above in personal piety and devotion to Christ — Abraham Rezeau Brown (1808-1833, age 24). The New Jersey-born eldest son of Isaac Van Arsdale Brown, and friend of James Brainerd Taylor, Rezeau, as he was known, was a gifted student who was brought up in his father’s academy (originally known as Maidenhead Academy, now Lawrenceville School), and was clearly gifted early in life. His longtime “particular friend” (1830 letter to John Hall) and biographer, James Waddel Alexander, wrote that he joined the junior class at the College of New Jersey (Princeton) at age 15 and graduated two years later with the highest literary honors. Rezeau was always of a “weak” and frail constitution, and it was poor health that took him to his Savior at the tender of age of 24. But as Alexander wrote, quoting John Newton, “Tell me not how he died, but how he lived.” And thus we shall endeavor here to do so.

It is Rezeau himself, through manuscripts found after his death, who tells us that he was not a devout Christian early on, but something remarkable happened.

There has, no doubt, happened a great change in my character, which I date in March 1S27. I was before that a mere worldling, careless of eternity, thoughtless of my own eternal interests, and of those around me, a profane swearer. Sabbath breaker, and every thing else that is wicked; though only to that degree which was quite consistent with a decent exterior, and what were considered quite regular and moral habits in a young man. At the time mentioned, I was led in a most sudden and surprising way, when I was alone one evening, to look upon myself as a deeply depraved and guilty sinner, and to experience, in a lively manner, the feeling of my desert of hell. But in the course of a few days, I was enabled, as I thought, to cast myself on the Lord Jesus Christ as my Redeemer, and I felt through him a sweet sense of forgiveness and reconciliation with God.

After his conversion, although earlier inclined to the field of medicine, more and more he felt a strong inner call to the ministry. He pursued the study of languages (Hebrew, Syriac, Arabic, French, German) and ministerial studies at Yale and Princeton. He was naturally inclined to languages but also hoped to serve the gospel in foreign lands. He served from 1828 to 1831 as a tutor at Princeton Theological Seminary, and was licensed to preach the gospel in April, 1831. He served as stated supply for three different congregations located around Morgantown, Virginia (now West Virginia) from October 1831 to June 1832. The harsh winter and constant travel wore him down and he was recalled to Princeton and Trenton, New Jersey, where he continued to preach. He then joined J.W. Alexander as assistant editor of The Presbyterian in Philadelphia. He was making plans to take a trip to Europe in March 1833, when he became ill. It was an illness from which he never recovered, and on September 10, 1833, he entered the presence of his Lord. His funeral sermon was preached by J.W. Alexander from Revelation 22:3-5.

It was after that life-changing work of the Spirit in his soul in 1827 that Rezeau directed all of his energy and limited strength to this one goal - as Alexander wrote: “All his studies had this object; and it is worthy of remark, that he appeared always to study for God.” Notes found in his private memorandum book bear this out. After penning considerations on the right understanding of the call to the ministry, we read these lines written to summarize his planned course of study.

To this end, I would attend,

I. To the affairs of my soul.

II. To the affairs of my body.

III. To the affairs of my mind.

1. 1. To be much engaged in reading the Bible, in meditating and in prayer.

2. To improve opportunities of Christian intercourse.

3. To cultivate a Christian temper, and do every thing as conscious that the eye of God is directed to me, as well as the eye of the world.

4. To gain proper views of duty, and to act up to my convictions.

II. 1. To take regular exercise, morning and evening.

2. To be moderate in eating, &c.

3. To ‘keep my body under.’

III. In regard to objects of study.

1. The Bible.

2. Theology, as a science.

3. Books to aid the intellect, by their power of thought or some effective quality.

B. In regard to method,

1. Read twice every good book.

2. Read carefully, not caring so much to finish the volume as to gain knowledge.

3. Read pen in hand, noting striking thoughts, and recording such as throw light on points not hitherto understood.

C. In regard to writing. I wish to gain some facility as well as correctness in my composition for the pulpit and the press.

1. Analyses of Sermons.

2. Sermons.

3. Presbyterial Exercises.

4. Notes on remaining topics in Didactic Theology.

Another extract from his memorandum book gives witness to his experience in personal piety.

Monday, January 2, 1832. Another year is gone! Let me be excited by the remembrance of my failures in duty, sins, waste of time, slow advancement in piety and knowledge — let me be stimulated to future diligence in every good thing.

I would, in dependence on divine aid, this morning resolve,

1. To be more diligent in the pursuit of piety. And as I have most failed by the neglect of devotional reading of the scriptures, by wandering thoughts in prayer, and by permitting unholy thoughts and tempers to gain admission to my mind, I would resolve to pay special attention to these things.

2. I resolve to be more faithful in every public and private duty of the ministry. Especially in bearing such an exterior as to exhibit the influence, and commending the nature of religion; and in private and public admonition.

3. I resolve to attempt to do some good to some individual every day.

4. I resolve to study the Bible more than I have done, both critically and practically.

5. I resolve to press forward towards perfection, as much as possible here below; or in other words, to grow in grace.

His correspondence also bears witness to his faith: Writing to a relative who had just become a communicant church member he gives this counsel, based on personal experience:

In regard to personal piety, I find (as you will do) that prayer is the chief means of growth. Days devoted to prayer are very profitable; seasons of fasting and humiliation equally so. To pray much and yet be a cold Christian, is an anomaly I have never seen in the dealings of God with his church. The scriptures should take up much of your attention. Religious biography, and other religious books, are also worthy of regard and perusal. There is no royal road to manhood in Christ Jesus: we must grow by degrees, which will be greater or less in proportion to our diligence in the use of the means. Read Ephesians vi. 10—18. Philippians ill. 12—14. Romans xii. 1 —21. for some inspired directions.

We have the account of his private prayer dated July 26, 1832, which was for him a day of fasting and humiliation. And we have a meditation he wrote also in the summer of 1832 in which he critically evaluated the state of his soul. These personal devotional writings are nearly sermons, deeply humbling and convicting to read. They are too long to quote here, but the reader is encouraged (and forewarned!) to read them in J.W. Alexander’s memoir, which appeared in the October 1834 Biblical Repertory and Theological Review here, which is the source for most of this biographical record (a memoir which is also supplemented with letters from Isaac Van Arsdale Brown, Samuel Miller and Archibald Alexander). We have a few writings and translated works by Rezeau on his own page here. His story can only be briefly told in this post, but it is a story worth knowing. His candle burned brightly and briefly, but his memory is blessed forever.