(If the author links in this post are broken, please visit our Free PDF Library and click on the author’s page directly.)

What light would be thrown upon the dim past if we had to-day the diaries of Francis Makemie, Jedediah Andrews, Francis Doughty, Richard Denton or Matthew Hill. Had we the catechism which Makemie published, but which has absolutely disappeared, we should understand fully his attitude toward the Quakers and why he came into conflict with George Keith. Had we all the discussions and the letters which must have been written about the famous Adopting Act of 1729, how many precious hours of time in later years would have saved, misunderstanding avoided and the Church spared much restlessness and bad feeling. Could we but have the lost minutes of the Presbytery of Philadelphia from 1717 to 1733, the action of that body and the opinion of its members on the Adopting Act and other similar matters, might have proved mouth and wisdom to some of the men of later generations. Would it be more than the mere gratifying of an idle curiosity if we knew the reasons why the Presbyterians did not have a conference with the Baptists after having requested it and with whom they had worshipped in the Barbadoes Store, Philadelphia, from 1695 to 1698? If we could but see the lost page or pages of the first minutes of the Presbytery of Philadelphia, it would settle for the Church the question of time and perhaps the question as to the declaration of doctrine and the attitude of the early fathers to the Confession of Faith. If we could but read 'the loving letters from Domine Frelinghuysen,' it might reveal to us the secret as to the change in the ministry of Gilbert Tennent to a more evangelistic style of preaching. -- William L. Ledwith, "The Record of Fifty Years, 1852-1902: Historical Sketch of the Presbyterian Historical Society" in Journal of Presbyterian History, Vol. 1, No. 6, p. 404

The Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia was built to preserve the records and artifacts of Presbyterian history, and provides climate-controlled record storage services, along with fire protection, and other document preservation resources.

At Log College Press, we delight in bringing old, dusty, classic American Presbyterian works into the light of day again for a new generation to appreciate. But there are some works that are simply lost to history, as painful for we bibliophiles to admit, and as William Ledwith has shown us already (the Presbyterian Historical Society was founded mainly to protect and preserve the treasures of Presbyterian church history). There are works known to exist at one time that have simply disappeared from the stage before the advent of digital imaging. These include diaries, Presbytery minutes, letters, and even entire books.A few examples which pertain to Log College Press authors:

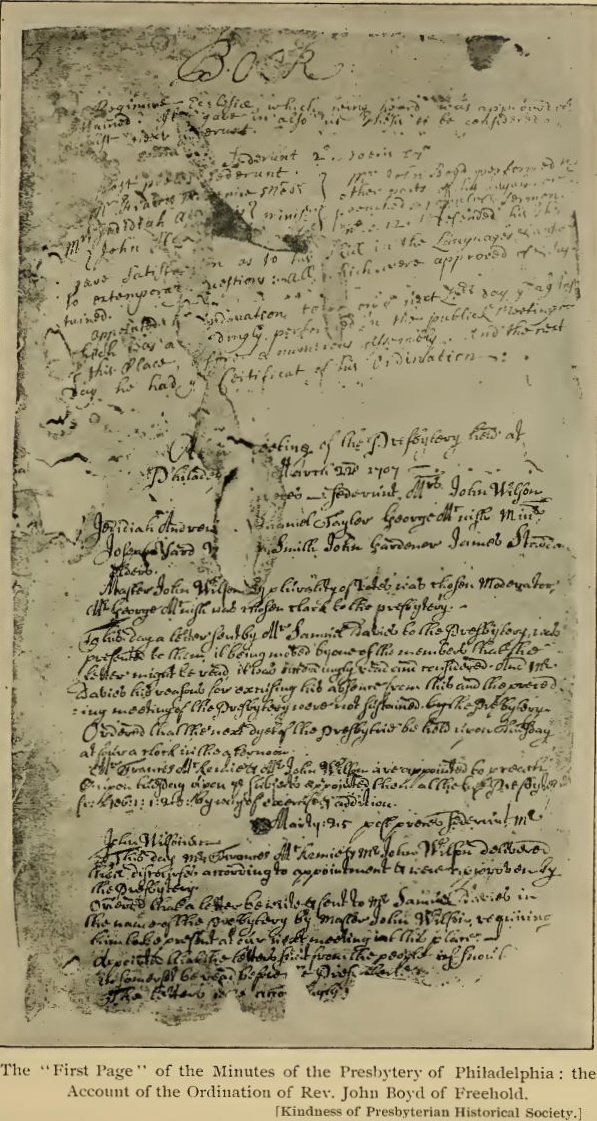

The first two pages of the first Presbytery’s Minute Book, which describe the first meeting, are lost to history. Pictured above is page 3 of the Minute Book, which gives an account of the ordination of John Boyd.

Francis Makemie - Besides the aforementioned Catechism, and his personal Diary, which are both gone, Makemie was accused by Lord Cornbury (who had previously tried him for preaching without a dissenters’ license and lost) with authorship of a 1707 New Jersey publication titled Forget and Forgive — of which Makemie denied authorship — for apparently slanderous remarks directed at him contained within. That book, which would certainly shine light on the ongoing dispute between Makemie (even if he was not the author) and Lord Cornbury, is simply nowhere to be found today.

Alexander Craighead - The first American Covenanter minister has left us some remarkable writings, but there are some gaps in his bibliography as well. His 1742 Discourse Concerning the Covenant is, strangely, missing eight pages. Moreover, no copy of an anonymous 1743 pamphlet thought to be published by him has survived after it was condemned by the Synod of Philadelphia for seditious principles. Considering his known published views on resistance to British tyranny, and the influence he had posthumously on the 1775 Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, this missing pamphlet constitutes a rather large gap in our understanding of a fascinating colonial Presbyterian.

Titus Basfield - Basfield was a former slave who studied at what is now known as Franklin College, where he was mentored by the college president and Associate Presbyterian pastor John Franklin. John Bingham (later the architect of the 14th Amendment) was a fellow student and close friend of Basfield with whom he carried on a correspondence of 40 years. Bingham's letters to Basfield were destroyed in the 1990s, after John Campbell, a private collector who owned them, died, and his widow threw them away (source: Gerard N. Magliocca, American Founding Son: John Bingham and the Invention of the Fourteenth Amendment, p. 197).

Samuel Davies - At one point during the ministry of Davies in Virginia, a writer who took the pen name “Artemas” attempted to “lampoon” Davies by association with alleged excesses related to the Great Awakening, including “a copious flow of tears” and “fainting and trembling” by some under his ministry. Davies responded with a pamphlet titled A Pill For Artemas, which according to a 19th century anonymous writer (“ A Recovered Tract of President Davies,” The Biblical Repertory and Princeton Review (1837), Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 363-364), “evinced the power of his sarcasm.” Davies sought a middle ground between extremes of lukewarmness and frenzied ecstasy in his hearers as the received the word of truth and responded appropriately. In any case, although the anonymous writer above said he had seen Davies’ pamphlet, George H. Bost wrote in 1942 that “Both pamphlets seem to have been lost” (Ph.D. dissertation titled Samuel Davies: Colonial Revivalist and Champion of Religious Toleration, p. 53).

So while we will continue to hunt for the interesting, rare and special works pertaining to American Presbyterianism to make them available at Log College Press, sadly, there are some things that are apparently lost to history. Would it be wonderful though, to find something thought to be lost in a drawer or attic somewhere? A church historian can dream, can’t they?