Receive our blog posts in your email by filling out the form at the bottom of this page.

One fascinating feature found within the writings of early American Presbyterians is the window some authors have given us to key moments in history. Amidst the doctrinal and devotional literature are records and observations, speeches, sermons, diary entries, letters and more that tell future generations, including ours, what it is like to be present at some of the most momentous historical events in the annals of America and the world.

One of the earliest Presbyterians in America was Alexander Whitaker, a chaplain who arrived at the Jamestown colony in Virginia in 1611, and who ministered to the Indian princess Pocahontas. He reported in a June 18, 1614 letter to his cousin William Gouge, later a Westminster Divine, concerning both her conversion to Christianity and her marriage to John Rolfe: “But that which is best, one Pocahuntas or what Matoa the daughter of Powhatan, is married to an honest and discreete English Gentleman Master Rolfe, and that after she had openly renounced her Country Idolatry, professed the faith of Jesus Christ, and was baptised; which thing Sir Thomas Dale had laboured a long time to ground in her.”

This portrait of The Baptism of Pocahontas by John Gadsby Chapman (1840), which shows Alexander Whitaker administering the sacrament, hangs in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol Building, Washington, District of Columbia.

Reportedly, among the 56 signers of the U.S. Declaration of Independence at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, twelve were Presbyterians, including Richard Stockton and John Witherspoon, the only clergyman present. Witherspoon also had a hand at another historical moment - the signing of the Articles of Confederation.

Signature of John Witherspoon on the 1776 U.S. Declaration of Independence (Witherspoon signed it on August 2, 1776).

Signature of John Witherspoon on the 1781 Articles of Confederation (New Jersey delegates signed the document on November 26, 1778).

Samuel Miller (then known as “Sammy”) was a young witness to history having been present at the State House in Philadelphia (Independence Hall) at the time of the 1787 Constitutional Convention. He watched as George Washington, and many other founding fathers, some of whom were friends of his father, John Miller, entered and departed while the work of preparing the US Constitution was going on. He was also a student at the University of Pennsylvania in 1789 while the first General Assembly of the PCUSA was meeting and working to revise the standards of the church. Miller’s friend — and later, colleague — John Rodgers played an important role at that Assembly (Miller was Rodgers’ biographer). He also developed close ties at this time to Ashbel Green, whose advice and counsel to young Miller would prove important as he entered upon his theological studies.

Junius Brutus Steams, Washington as Statesman at the Constitutional Convention (1856)

One of the most amazing meteor showers recorded in history took place in during the night and early morning of November 12-13, 1833. There were many who witnessed the Leonid meteor storm in which between 50,000 and 150,000 meteors fell each hour, one of whom was David Talmage, the father of Thomas De Witt Talmage, who later told his father’s story in a sermon.

Engraving of the 1833 Leonid Meteor Shower by Adolf Vollmy (1889), based on the painting by Karl Jauslin.

Albert Williams, who founded the First Presbyterian Church of San Francisco, California, wrote about the series of fires that plagued the city in 1851 in A Pioneer Pastorate (1879): “So frequent and periodical were these fires, that they came to be regarded in the light of permanent institutions. Fears of a recurrence of the dread evil, in view of the past, were not long in waiting for fulfilment. On the anniversary of the fire of the 4th of May, 1850, came another on the 4th of May, 1851, the fifth general fire. The city was appalled by these repeated calamities. And more, it began to be a confirmed conviction that they were not accidental, but incendiary. On the 22d of June, 1851, the sixth, and, happily the last general fire, and severest of all, occurred. The fact that the point of the beginning of this fire was in a locality quite destitute of water facilities, with other attending circumstances, left hardly a remaining doubt of its incendiary character.”

Depiction of the June 22, 1851 San Francisco Fire.

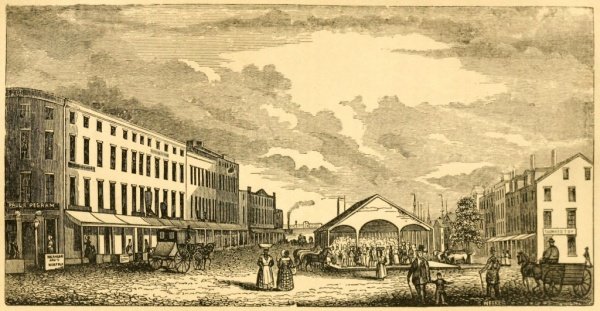

The summer of 1855 was devastating to the city of Norfolk, Virginia. George D. Armstrong, pastor of the First Presbyterian Church, endured the epidemic of yellow fever that decimated the city. He stayed during the outbreak to minister to the sick, often serving them for over 15 hours per day, but lost his wife, one daughter, a nephew and a sister-in-law to the disease. He wrote The Summer of the Pestilence: A History of the Ravages of the Yellow Fever in Norfolk, Virginia (1856).

Market Square, Norfolk, Virginia.

The War Between the States saw Presbyterians on both sides of the conflict. Robert L. Dabney, Stonewall Jackson’s chief of staff and biographer, wrote What I Saw of the Battle of Chickahominy (1872) concerning the June 27, 1862 conflict also known as the Battle of Gaines' Mill in Hanover County, Virginia. Later that year, on the same day as the Battle of Antietam (or Sharpsburg, Maryland) [September 17, 1862], a terrible tragedy took place in at the Allegheny Arsenal in Lawrenceville, Pennsylvania, now a neighborhood in Pittsburgh. Three consecutive explosions rocked the facility and 78 people were killed along with 150 injured, making it the worst civilian and industrial accident of the war. Presbyterian minister Richard Lea was at his church one block away, who immediately rushed over to render aid. Eleven days later, he preached a Sermon Commemorative of the Great Explosion at the Allegheny Arsenal. Before the war ended, Henry Highland Garnet made history in Washington, D.C. by becoming the first African-American to address the House of Representatives on February 12, 1865. His sermon called for the death of slavery and freedom for all American citizens.

Henry Highland Garnet preaching to Congress.

Thomas De Witt Talmage had a very successful ministry at the Brooklyn Tabernacle in New York. But the congregation was challenged by the occasions when their building was destroyed by fire, not once, but three times — in 1872, 1889, and 1894. After the third conflagration, Talmage retired from that pastorate. As he began a trip around the world, he wrote to his friends: “Our church has again been halted by a sword of flame. The destruction of the first Brooklyn Tabernacle was a mystery. The destruction of the second a greater profound. This third calamity we adjourn to the Judgment Day for explanation. The home of a vast multitude of souls, it has become a heap of ashes. Whether it will ever rise again is a prophecy we will not undertake. God rules and reigns and makes no mistake. He has his way with churches as with individuals. One thing is certain; the pastor of Brooklyn Tabernacle will continue to preach as long as life and health last. We have no anxieties about a place to preach in. But woe is unto us if we preach not the Gospel! We ask for the prayers of all good people for the pastor and people of Brooklyn Tabernacle.”

Brooklyn Tabernacle after the fire.

On May 31, 1889, after days of heavy rain, the South Fork Dam upstream of Johnstown, Pennsylvania burst leading to the deaths of over 2,000 people. David J. Beale was one of the survivors and his account of the tragedy is gripping: Through the Johnstown Flood (1890).

Debris from the Johnstown Flood.

At 5:12 am local time on April 18, 1906, the city of San Francisco was rocked by one of the deadliest earthquakes ever to strike the United States. Over 3,000 people were killed and 80% of the city was destroyed. Among those affected were the Chinese girls who were being cared for at the Occidental Board of Foreign Missions after having been rescued from involuntary servitude. Superintendent Donaldina Cameron was able to, shepherd those girls to the premises of the San Francisco Theological Seminary after the earthquake. Edward A. Wicher, a professor at the seminary, wrote an appeal for emergency funds to help the suffering, which Cameron co-signed. Cameron later wrote of the blessings that God wrought in the midst of that tragedy: “‘As the night brings out the stars’ so through the shadow of disaster there shines for the Chinese Rescue Home the unfailing light of God's love and peace, and we are happy.”

The Occidental Board of Foreign Missions Headquarters after the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake.

From 1915 to 1917, approximately 1 million Armenians were slaughtered by Ottoman forces. The Armenian Genocide was documented in part by American missionaries, such as as William Ambrose Shedd and his wife Mary Lewis Shedd, Mary A. Schauffler Labaree Platt, author of The War Journal of a Missionary in Persia (1915), and Frederick G. Coan, author of Yesterdays in Persia and Kurdistan (1939). Rev. Shedd: “It lies with us to see that the blood shed and the suffering endured are not in vain. May God grant and may we who know so well the wrongs that have been borne, so labor that the cause of these wrongs be removed. That will be done when Christ rules in the hearts of those who profess His name and is acknowledged by all, not merely as a great prophet but as the Saviour for Whose coming prophecy prepared the way, Who is the fulfillment of revelation, and in Whom human destiny will find its goal.”

Ottoman troops guard Armenians being deported. Ottoman Empire, 1915-1916.

Wilson P. Mills was an American missionary who served also in a diplomatic capacity during the 1937-1938 “Rape of Nanjing,” a massacre by Japanese soldiers that resulted in the deaths of somewhere between 40,000-300,000 civilians in occupied Nanjing, China. His efforts to help arrange a truce are described in letters to his wife dated January 22/24 and January 31, 1938. The story of his eyewitness account of the Japanese occupation of the city and the reign of terror that existed is told sequentially in letters from January to March 1938. For his role in protecting the 250,000 citizens of the Nanjing Safety Zone, Mills received the Order of the Green Jade, the highest honor given to Westerners by the Chinese government.

Scene from the Nanjing Massacre.

Examples of eyewitnesses to history among American Presbyterian could be greatly multiplied. So many of them have left us a valuable record of some of the most momentous events in our history, “all [of which] have a common place in the great scheme of Providence” (Henry A. Boardman, God's Providence in Accidents (1855).