Receive our blog posts in your email by filling out the form at the bottom of this page.

"He that will not honor the memory, and respect the influence of Calvin, knows but little of the origin of American liberty." — George Bancroft, Literary and Historical Miscellanies (1855), p. 406

The central thesis of this book — that John Calvin and his Genevan followers had a profound influence on the American founding — runs counter to widespread assumptions and rationale of the American experiment in government. — David W. Hall, The Genevan Reformation and the American Founding (2003), p. vii

On the Fourth of July, which is not only the date celebrated as the birth of the United States in 1776, but also the date on which Log College Press was founded in 2017, we pause to remember how God has dealt graciously with this nation in large part through the influence of the doctrines of grace and the principles of civil liberty which are associated with Calvinism.

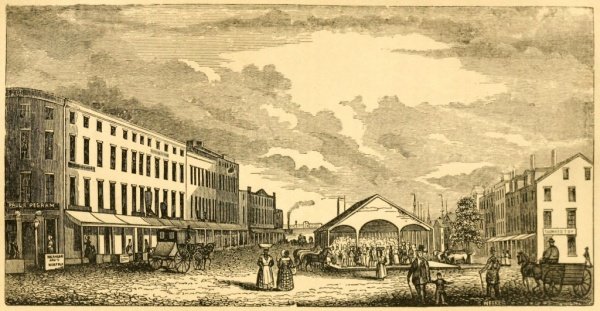

American history has many streams running through it, including the Native American population, Spanish exploration, African-American slaves, and much more, but it cannot be denied that in the colonial era and in the early part of the republic, American principles and character were largely fashioned by the Protestant European settlers who came to this country and, looking to Scripture as their foundation, enacted laws, promoted education and even fought for freedom, on the basis of ideas taught in John Calvin’s Geneva.

To demonstrate this premise — which historically was unquestioned, but has been increasingly challenged in recent years — we will extract from the writings of some authors on Log College Press, and others, to show that many of America’s founding principles can be traced to the Calvinism that brought French Huguenots to Florida and South Carolina in 1562; English Anglicans and Presbyterians to Jamestown, Virginia in 1607; Pilgrims and Puritans to Massachusetts beginning in 1620; the Dutch Reformed to New Netherland (New York) in the 1620s; the Scotch-Irish, such as Francis Makemie in the 1680s, to Virginia and Pennsylvania; and the German Reformed settlers who, as did John Phillip Boehm in 1720, arrived in Pennsylvania and other ports of entry. Although painting a picture with broad strokes, and not at all unmindful of the secular character of this nation today under principles enshrined in the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights, it is worthwhile to consider how Geneva influenced the founding of America more than any other source. It has been well said by some that “knowledge of the past is the key to the future.”

Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, The Mayflower Compact, 1620

Egbert W. Smith writes, in a chapter titled “America’s Debt to Calvinism,” that:

If the average American citizen were asked, who was the founder of America, the true author of our giant Republic, might be puzzled to answer. We can imagine his amazement at hearing the answer given to this question by the famous German historian, [Leopold von] Ranke, one of the profoundest scholars of modern times. Says Ranke, ‘John Calvin was the virtual founder of America.’” — E.W. Smith, The Creed of Presbyterians (1901), p. 119

In a lecture given by Philip Schaff in 1854, he stated:

The religious character of North America, viewed as a whole, is predominantly of the Reformed or Calvinistic stamp…To obtain a clear view of the enormous influence which Calvin's personality, moral earnestness, and legislative genius, have exerted on history, you must go to Scotland and to the United States. — Philip Schaff, America: A Sketch of the Political, Social, and Religious Character of the United States of North America (1855), pp. 111-112

Nathaniel S. McFetridge devotes a chapter in his most famous book, Calvinism in History, to the influence of Calvinism as a political force in American history, and argues thus:

My proposition is this — a proposition which the history clearly demonstrates: That this great American nation, which stretches her vast and varied territory from sea to sea, and from the bleak hills of the North to the sunny plains of the South, was the purchase chiefly of the Calvinists, and the inheritance which they bequeathed to all liberty-loving people.

If would be almost impossible to give the merest outline of the influence of the Calvinists on the civil and religious liberties of this continent without seeming to be a mere Calvinistic eulogist; for the contestants in the great Revolutionary conflict were, so far as religious opinions prevailed, so generally Calvinistic on the one side and Arminian on the other as to leave the glory of the result almost entirely with the Calvinists. They who are best acquainted with the history will agree most readily with the historian, Merle D’Aubigne, when he says: ‘Calvin was the founder of the greatest of republics. The Pilgrims who left their country in the reign of James I., and, landing on the barren soil of New England, founded populous and mighty colonies, were his sons, his direct and legitimate sons; and that American nation which we have seen growing so rapidly boasts as its father the humble Reformer on the shores of Lake Leman [Lake Geneva].’” — N.S. McFetridge, Calvinism in History (1882), pp. 59-60

W. Melancthon Glasgow, referencing the great American historian George Bancroft, says:

"Mr. Bancroft says: 'The first public voice in America for dissolving all connection with Great Britain came not from the Puritans of New England, the Dutch of New York, nor the Planters of Virginia, but from the Scotch-Irish Presbyterians of the Carolinas.' He evidently refers to the influence of Rev. Alexander Craighead and the Mecklenburg Declaration: and this influence was due to the meeting of the Covenanters of Octorara, where in 1743, they denounced in a public manner the policy of George the Second, renewed the Covenants, swore with uplifted swords that they would defend their lives and their property against all attack and confiscation, and their consciences should be kept free from the tyrannical burden of Episcopacy....It is now difficult to tell whether Donald Cargill, Hezekiah Balch or Thomas Jefferson wrote the National Declaration of American Independence, for in sentiment it is the same as the "Queensferry Paper" and the Mecklenburg Declaration." — W. Melancthon Glasgow, History of the Reformed Presbyterian Church in America (1888), pp. 65-67

William H. Roberts, in a chapter on “Calvinism in America,” wrote:

Politically, Calvinism is the chief source of modern republican government. That Calvinism and republicanism are related to each other as cause and effect is acknowledged by authorities who are not Presbyterians or Reformed…The Westminster Standards are the common doctrinal standards of all the Calvinists of Great Britain and Ireland, the countries which have given to the United States its language and to a considerable degree its laws. The English Calvinists, commonly known as Puritans, early found a home on American shores, and the Scotch, Dutch, Scotch-Irish, French and German settlers, who were of the Protestant faith, were their natural allies. It is important to a clear understanding of the influence of Westminster in American Colonial history to know that the majority of the early settlers of this country from Massachusetts to New Jersey inclusive, and also in parts of Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas, were Calvinists.” — William H. Roberts in Philip Vollmer, John Calvin: Theologian, Preacher, Educator, Statesman (1909), pp. 202-203

Speaking of the Scotch-Irish, Charles L. Thompson wrote:

Did they abandon homes that were dear to them in Scotland first and then in Ireland? It was done at the call of God. They wanted homes for themselves and their children; but it was only that in them there might be a free development of the faith for which their fathers and they had suffered. Nor was their religion a thing of either forms or sentiment. It was grounded in Scripture. The family Bible was the charter of their liberties. To seek its deepest meanings was their delight. They, therefore, brought to to their various settlements in the new world a knowledge of the Calvinism which they had found in their Bibles, and a devotion to the forms in which it found expression giving definite doctrinal character to all their communities — character by which their various migrations may be easily traced. Whether in Nova Scotia, in Pennsylvania, in Kentucky and Tennessee, or wherever their pioneer footsteps led them, the stamp of their convictions, from which no ‘wind of doctrine’ and no ‘cunning craftiness’ could draw them, is seen in all their social life and on all their institutions. Almost universally they were Presbyterians and they are the dominant element in the Presbyterian Church today.

Alike among the Puritans, the Dutch and the Scotch-Irish, it was Calvinism which was the prevailing doctrine. Its relation to the life of our republic has often been recognized. — Charles L. Thompson, The Religious Foundations of America (1917), pp. 242-243

Loraine Boettner, in a section on Calvinism in America, quotes George Bancroft in regards to the American War of Independence:

With this background we shall not be surprised to find that the Presbyterians took a very prominent part in American Revolution. Our own historian Bancroft says: “The Revolution of 1776, so far as it was affected by religion, was a Presbyterian measure. It was the natural outgrowth of the principles which the Presbyterianism of the Old World planted in her sons, the English Puritans, the Scotch Covenanters, the French Huguenots, the Dutch Calvinists, and the Presbyterians of Ulster.” So intense, universal, and aggressive were the Presbyterians in their zeal for liberty that the war was spoken of in England as “The Presbyterian Rebellion.” An ardent colonial supporter of King George III wrote home: “I fix all the blame for these extraordinary proceedings upon the Presbyterians. They have been the chief and principal instruments in all these flaming measures. They always do and ever will act against government from that restless and turbulent anti-monarchial spirit which has always distinguished them everywhere.” When the news of “these extraordinary proceedings” reached England, Prime Minister Horace Walpole said in Parliament, “Cousin America has run off with a Presbyterian parson.” — Loraine Boettner, The Reformed Doctrine of Predestination (1932), p. 383

Speaking of Calvinism’s influence on America, H. Gordon Harold wrote:

Now back of every great movement lie its proponents. Who were the people that fostered rebellion and revolution in the New World? Who spoke openly against the tyrannies and indignities they experienced? Who stepped forward with ready hearts, willing to die in resistance to the injustices meted out to them in the wilderness of this remote continent? They were mostly as follows: Huguenots from France; men of the Reformed faith, presbyterians of the Continent, who had come from the Palatinate, Switzerland, and the Low Countries; Lutherans who had fled the agonies of the Thirty Years’ War; German Baptists who had endured persecution; and Presbyterians and Seceders (ultra-Presbyterians) from Scotland and Ulster; also the Puritan Congregationalists from England. Practically all of these were Calvinists, or neo-Calvinists, and a large number of them were Ulster-Scotch Presbyterians. — H. Gordon Harold in Gaius J. Slosser, ed., They Seek a Country: The American Presbyterians (1955), pp. 151-152

Douglas F. Kelly had this to say about the “Presbyterian Rebellion” of 1776:

The gibe of some in the British Parliament that the American revolution was “a Presbyterian Rebellion” did not miss the mark. We may include in “Presbyterian” other Calvinists such as New England Congregationalists, many of the Baptists, and others. The long-standing New England tradition of “election day sermons” continued to play a major part in shaping public opinion toward rebellion toward England on grounds of transcendent law. Presbyterian preaching by Samuel Davies and others had a similar effect in preparing the climate of religious public opinion for resistance to royal or parliamentary tyranny in the name of divine law, expressed in legal covenants. Davies directly inspired Patrick Henry, a young Anglican, whose Presbyterian mother frequently took him to hear Davies.” — Douglas F. Kelly, The Emergence of Liberty in the Modern World: The Influence of Calvin on Five Governments From the 16th to the 18th Centuries (1992), pp. 131-132

At Log College Press, in appreciation of this great Calvinistic heritage which was bequeathed to 21st century Americans by Geneva and those who were inspired by her to come to these shores, we wish you and yours a very happy Fourth of July! And if we have not already “taxed” our readers’ patience without their consent (this blog post is admittedly longer than most), in the spirit of the day, we offer more to read from the following blog posts from the past. Blessings to you and yours!

July 4, 2022 - Fourth of July Celebration at Log College Press

July 3, 2021 - American Independence and Presbyterians

July 4, 2020 - W.P. Breed: Presbyterians and the Revolution

July 4, 2019 - Freedom’s Cost

July 4, 2018 - American Presbyterians Wish You a Happy Independence Day!